Opinion

The Oracle: Ethnic Nationalities and Emerging Challenges in Nigeria (Pt. 2)

Published

3 years agoon

By

Eric

By Mike Ozekhome

INTRODUCTION

ETHNIC CONFLICTS AND NIGERIA

Nigeria is befuddled with grave ethnic conflicts. This deprives her of the much needed National Unity. No Nation can ever develop along those fundamental fault lines of ethnic disharmony. National unity is thereby endangered.

National unity is the most important factor that holds a country together. It occurs when people live and work together in harmony and love. It allows leaders to harvest citizens’ commitment and contribution to nation-building and national development. It serves as one of the most effective weapons of preventing internal conflicts which are capable of draining the internal resources of a nation and derailing its progress. Most people do not care about a country parting or breaking up. No country can develop meaningfully without an idea of national unity. Nigeria, according to Prof Onigu Otite, Nigeria has 374 ethnic groups, speaking over 500 languages. This ought, ordinarily, to amplify her rich plurality and diversities in a positive way. But the reverse appears to be the case.

These groups are broken down along religious, linguistic and tribal lines. These divisions had always existed, but were further broken down at independence into a multi-ethnic nation state.

With these centripetal and centrifugal divisions, the nation has been battling with the problem of ethnicity on the one hand, and the problem of ethno-religious conflicts on the other, as has been witnessed severally when ethnic and religious intolerance led to ethno-religious conflicts.

Even from the atavistic tone of the names of organizations championing the Niger Delta struggles since independence, the mobilization efforts sketched above present a challenge for analysts, many of whom have simply interpreted the motivations and agendas of grassroots struggles in the Niger Delta as primordial, exclusionist and particularistic; in other words, as fundamentally ethnic and capable of undermining national renaissance. It is important to mention here that, ‘ethnic group’ refers to the social identity built on the mythopoetry of language, history, cultural practices, myths, symbols and (in the case of Nigeria also) geographic location. This working definition in no way endorses primordialism ideas of frozen or fossilized identities, and does certainly take account of the constructivist notion of changeability and manipulability. It does not accept extreme constructivist ideas of ‘ethnic group’ as something entirely invented or fabricated.

A notable scholarly attempt to dissect the Niger Delta struggle and similar tendencies in other parts of Nigeria, which contains case analyses of the mobilization activities of the Ijaw Youth Council (IYC), Odwua People’s Congress (OPC), and Arewa People’s Congress (APC). Ikelegbe tries to show how, contrary to popular notions of ‘civil society’ as “the beacon of freedom, the fountain for the protection of civil rights and of resistance against state repression, the objectives, methods and roles” of ‘civil society’ organizations could undermine the democratic project. The IYC, which as earlier indicated, has been involved in the Niger Delta mobilization since the 1990s, is portrayed as only speaking the minds of the Ijaws and at least parts of the Niger Delta’ – a prime example of what the author terms ‘perverse’ civil society.

Accordingly, the author offers an insight into what the term ‘ethnic’ could mean, by contrasting it with ‘civic’ or ‘ideal’. He argues that ‘ethnic’ mobilization tends to be ‘sectional’, ‘criminal’, ‘anarchic’, ‘parochial’ and ‘centrifugal’. The three organizations in his analysis are therefore ethnic movements ‘masquerading as civil society’. This focus on the activities of formal activist organizations, rather than on the narratives and lived worlds of the ordinary people the organizations ‘represent’, presents analytical difficulties of its own, as shown later. For one thing, it makes it easy to cast local struggles as ‘sectional’ and ‘parochial’. The organizations are also portrayed as ‘criminal’ and ‘anarchic’ on account of their protest methodology. Their key protest strategy is believed to be ‘violence’. The ‘tendency for aggrieved groups to take up arms in their encounters with the state and other groups and the support the groups enjoy from ‘civil groups of elders and political leaders’ are deplored. This is despite sociological arguments that violence is sometimes a ‘smoke from the fire’ of unjust public institutions, state policies and the political process, or injustices in the corporate and transnational spheres.

Cesarz et al also hinted that the Niger Delta mobilization could be disguised ethnicity. For them interethnic violence is a longstanding feature of the oil-rich Niger Delta, and Ijaw militancy in particular is viewed as a risk to international oil interests and to Nigeria’s future as a united and stable polity. Local groups, the authors suggest, are no longer to be seen as ‘a loosely organized ethnic, sporadic movement, they are now an ‘armed ethnic militia’ capable of derailing Nigeria’s new-found democracy. Reacting to that line of analysis are Douglas et al, who challenge the use of the term ‘ethnic militia’ to describe local activist groups. Such a depiction, they argue, misrepresents the essence of the Niger Delta struggle.

However, whether the two groups of analysts are operating from different epistemic platforms is another matter entirely. For one thing, Douglas et al view the emerging coalition-building efforts among community groups in the Niger Delta as constituting a ‘bulwark against the ethnic majorities’. Now one will simply ask, what is the empirical basis for suggesting that ordinary people in the Delta as mobilizing against the ‘ethnic majorities’, and how is this view different from Cesarz et al’s suggestion that the local activists are involved in a disguised ‘ethnic’ warfare?

There is also the argument that while local struggles might stem from economic and political disparities in Nigeria, they might fundamentally be attributable to “communal pressures that have characterized the Niger Delta and many other parts of Nigeria”. Welch calls these ‘communal pressures matters of ethnic self-determination, maintaining that economic and political change in a multi-ethnic milieu like Nigeria invariably triggers ethnic conflict.

Short of portraying Nigeria’s ethnic nationalities as fundamentally incompatible social groupings, he posits that Nigeria as an entity ‘came into being long before a substantial number of its residents felt themselves to be “Nigerians”. While Welch uses this essentialist analysis to interrogate the concept of individual rights and to make a contribution to the ‘group rights’ debate, concerns might be raised as to whether his argument does not in fact distort the complexity of the Niger Delta crisis. A more nuanced insight into the Niger Delta conflict might be gained from Bangura’s ‘three crises’ of post-colonial African state – those of ‘capacity’, ‘governance’ and ‘security’. The works of Osadolor, Agbola and Alabi, Agiobenebo and Aribaolanari and Uga, among others, are more explicit in ‘revealing’ what it is that engenders disaffection between the oil-producing region and the major ethnic nationalities. They argue that it is the ‘majority groups’ that determine the framework for petroleum exploitation (as well as interethnic relations and political governance) in Nigeria and unfairly profit from it. As Agiobenebo and Aribaolanari put it: “the ethnic minorities of the Niger Delta are treated as objects (property) owned by the majority groups to be dealt with according to their whims and caprices”. There is even an implicit (but erroneous) assumption by these analysts that it is on behalf of their own people that the major ethnic groups ‘control’ political power in Nigeria and suppress socio-economic development in the Niger Delta. It is noteworthy that Obi places the protests and demands of Niger Delta groups such as MOSOP within the rubric of grassroots struggles for broader societal transformation. He suggests that the Niger Delta conflict must be seen in terms of its connection to “broader popular social struggles for empowerment and democracy”. This line of analysis, which forms part of what Idemudia and Ite call an ‘integrated explanation’, and which speaks directly to the conflict’s deeper social character, has been obscured in so much of the literature.

The above review also shows that while some analysts have acknowledged that the issues in the Niger Delta struggle transcend ‘local concerns’, and that the struggle makes a strong statement on the pains that a ‘distant state’ has inflicted on the Nigerian society as a whole, the failure of governance at the national level is not given the explanatory status it deserves. This begs the question as to why the search for empirical information on grassroots struggles such as those in the Niger Delta almost inevitably proceeds from an ethnic frame of reference. Could it be, as Mamdani has conjectured concerning conflicts in Africa, that the bifurcated nature of the state shaped under colonialism, and of the politics it shaped in turn, had now appeared in the theory that tried to explain it?

However, the next section sheds some light on this question. Some of the aforementioned analyses, especially the strand that suggests that the Niger Delta struggle is a way of ‘striking back’ at, or at least resisting, the major ethnic nationalities, who appropriate the ‘lion’s share’ of Nigeria’s petroleum revenues at the expense of the oil-producing region, have all the ingredients of the ‘competition theses of ethnic mobilization. I will also opine here that, where state policies appear to disproportionately benefit some regions of a multi-ethnic society, heightened ethnic awareness and collective ethnic action across the society become common tendencies in the society in question. As Feagin puts it, ‘competition occurs when two or more ethnic groups attempt to secure the same resources’; besides, ‘ethnic competition destabilizes group relations.

Seen from such a perspective, the geologic fact of petroleum not being evenly distributed across Nigeria can be a basis for ethnic competition. However, the competition becomes exacerbated and produces invidious socio-political outcomes for the entire polity where state policies driving the utilization of resources seem to favor some geo-ethnic groups while disadvantaging the others.

The works of Osadolor, Agbola and Alabi, Agiobenebo and Aribaolanari and Uga generally make this point. Since groups in the Niger Delta could not be mobilizing simply for the sake of doing so, the insight that these analysts attempt to proffer is that the Niger Delta mobilisation must be for the maximization of sectional interests, with the non-producing ethnic groups a target of their grievance. Also, Akpan stated thus, It would of course, not be correct to assume that the ‘unfair’ appropriation of national resources by some leaders from the major ethnic groups has been fundamentally for the ‘greater good’ of ordinary people in their geo-ethnic regions.

Flowing from all of these, in a bid to address these ethnic nationalities challenges, the CIVIL SOCIETY LEGISLATIVE AND ADVOCACY CENTRE (CISLAC) in collaboration with FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG (FES) NIGERIA with support from the European Union recently held a stakeholder’s consultative forum on Peace and Security Challenges in Nigeria themed “Ethnicity, Ethnic Crises and National Security: Casual Analysis and Management Strategies”. The stakeholders drawn from both military, lawmakers, security and paramilitary organizations, as well as civil societies, tackled the causes of such ethnic crisis which is presently breeding security challenges across the country and in essence threatening the corporate existence of Nigeria. Essentially, the stakeholders advocated for dialogue of all ethnic nationalities and inclusiveness if the issues are to be addressed holistically.

Interestingly, the organizer’s objective for the forum was to cross fertilize ideas, analyze gaps and the threats of separatists’ agitation across the country and its implication on national security and develop a policy recommendation; to also raise awareness on implication of ethnic champions and its threats to national security; and enhance cooperation and collaboration between state and non-state actor as a collective response to unionism.

FUN TIMES

“I will never date short guys again, imagine Ushers in my church were dragging my boyfriend to children’s Department”. –Anonymous

THOUGHT FOR THE WEEK

“True equality means holding everyone accountable in the same way, regardless of race, gender, faith, ethnicity – or political ideology”. (Monica Crowley).

Related

You may like

Opinion

A Holistic Framework for Addressing Leadership Deficiencies in Nigeria, Others

Published

1 day agoon

February 6, 2026By

Eric

By Tolulope A. Adegoke PhD

“Effective leadership is not a singular attribute but a systemic outcome. It is forged by institutions stronger than individuals, upheld by accountability with enforceable consequences, and sustained by a society that demands integrity as the non-negotiable price of power. The path to renewal—from national to global—requires us to architect systems that make ethical and competent leadership not an exception, but an inevitable product of the structure itself” – Tolulope A. Adegoke, PhD

Introduction: Understanding the Leadership Deficit

Leadership deficiencies in the modern era represent a critical impediment to sustainable development, social cohesion, and global stability. These shortcomings—characterized by eroded public trust, systemic corruption, short-term policymaking, and a lack of inclusive vision—are not isolated failures but symptoms of deeper structural and ethical flaws within governance systems. Crafting effective solutions requires a clear-eyed, unbiased analysis that moves beyond regional stereotypes to address universal challenges while respecting specific contextual realities. This document presents a comprehensive, actionable framework designed to rebuild effective leadership at the national, continental, and global levels, adhering strictly to principles of meritocracy, accountability, and transparency.

I. Foundational Pillars for Systemic Reform

Any lasting solution must be built upon a bedrock of core principles. These pillars are universal prerequisites for ethical and effective governance.

1. Institutional Integrity Over Personality: Systems must be stronger than individuals. Governance should rely on robust, transparent, and rules-based institutions that function predictably regardless of incumbents, thereby minimizing personal discretion and its attendant risks of abuse.

2. Uncompromising Accountability with Enforceable Sanctions: Accountability cannot be theoretical. It requires independent oversight bodies with real investigative and prosecutorial powers, a judiciary insulated from political interference, and clear consequences for misconduct, including loss of position and legal prosecution.

3. Meritocracy as the Primary Selection Criterion: Leadership selection must transition from patronage, nepotism, and identity politics to demonstrable competence, proven performance, and relevant expertise. This necessitates transparent recruitment and promotion processes based on objective criteria.

4. Participatory and Deliberative Governance: Effective leaders leverage the collective intelligence of their populace. This demands institutionalized channels for continuous citizen engagement—beyond periodic elections—such as citizen assemblies, participatory budgeting, and formal consultation processes with civil society.

II. Context-Specific Strategies and Interventions

A. For Nigeria: Catalyzing National Rebirth Through Institutional Reconstruction

Nigeria’s path requires a dual focus: dismantling obstructive legacies while constructing resilient, citizen-centric institutions.

· Constitutional and Electoral Overhaul: Reform must address foundational structures. This includes a credible review of the federal system to optimize the balance of power, the introduction of enforceable campaign finance laws to limit monetized politics, and the implementation of fully electronic, transparent electoral processes with real-time result transmission audited by civil society. Strengthening the independence of key bodies like INEC, the judiciary, and anti-corruption agencies through sustainable funding and insulated appointments is non-negotiable.

· Genuine Fiscal Federalism and Subnational Empowerment: The current over-centralization stifles innovation. Empowering states and local governments with greater fiscal autonomy and responsibility for service delivery would foster healthy competition, allow policy experimentation tailored to local contexts, and reduce the intense, often violent, competition for federal resources.

· Holistic Security Sector Reform: Addressing insecurity requires more than hardware. A comprehensive strategy must include community-policing models, merit-based reform of promotion structures, significant investment in intelligence capabilities, and, crucially, parallel programs to address the root causes: youth unemployment, economic inequality, and environmental degradation.

· Investing in the Civic Infrastructure: A functioning democracy requires an informed and engaged citizenry. This mandates a national, non-partisan civic education curriculum and robust support for a free, responsible, and financially sustainable press. Protecting journalists and whistleblowers is essential for maintaining transparency.

B. For Africa: Leveraging Continental Solidarity for Governance Enhancement

Africa’s prospects are tied to its ability to act collectively, using regional and continental frameworks to elevate governance standards.

· Operationalizing the African Governance Architecture: The African Union’s mechanisms, particularly the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), must transition from voluntary review to a system with meaningful incentives and consequences. Compliance with APRM recommendations could be linked to preferential access to continental infrastructure funding or trade benefits under the AfCFTA.

· The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) as a Governance Catalyst: Beyond economics, the AfCFTA can drive better governance. By creating powerful cross-border commercial interests, it builds domestic constituencies that demand policy predictability, dispute resolution mechanisms, and regulatory transparency—all hallmarks of sound leadership.

· Pan-African Human Capital Development: Strategic investment in continental human capital is paramount. This includes expanding regional centers of excellence in STEM and public administration, fostering academic and professional mobility, and deliberately cultivating a new generation of technocrats and leaders through programs like the African Leadership University.

· Consistent Application of Democratic Norms: Regional Economic Communities (RECs) must enforce their own democratic charters uniformly. This requires establishing clear, automatic protocols for responding to unconstitutional changes of government, including graduated sanctions, rather than ad-hoc diplomatic responses influenced by political alliances.

C. For the Global System: Rebuilding Equitable and Effective Multilateralism

Global leadership crises often stem from outdated international structures that lack legitimacy and enforceability.

· Reforming Archaic Multilateral Institutions: The reform of the United Nations Security Council to reflect 21st-century geopolitical realities is essential for its legitimacy. Similarly, the governance structures of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank must be updated to give emerging economies a greater voice in decision-making.

· Combating Transnational Corruption and Illicit Finance: Leadership deficiencies are often funded from abroad. A binding international legal framework is needed to enhance financial transparency, harmonize anti-money laundering laws, and expedite the repatriation of stolen assets. This requires wealthy nations to rigorously police their own financial centers and professional enablers.

· Fostering Climate Justice and Leadership: Effective global climate action demands leadership rooted in equity. Developed nations must fulfill and be held accountable for commitments on climate finance, technology transfer, and adaptation support. Leadership here means honoring historical responsibilities.

· Establishing Norms for the Digital Age: The technological frontier requires new governance. A global digital compact is needed to establish norms against cyber-attacks on civilian infrastructure, the use of surveillance for political repression, and the cross-border spread of algorithmic disinformation that undermines democratic processes.

III. Universal Enablers for Transformative Leadership

Certain interventions are universally applicable and critical for cultivating a new leadership ethos across all contexts.

· Strategic Leadership Development Pipelines: Nations and institutions should invest in non-partisan, advanced leadership academies. These would equip promising individuals from diverse sectors with skills in ethical decision-making, complex systems management, strategic foresight, and collaborative governance, creating a reservoir of prepared talent.

· Redefining Success Metrics: Moving beyond Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the primary scorecard, governments should adopt and be assessed on holistic indices that measure human development, environmental sustainability, inequality gaps, and citizen satisfaction. International incentives, like preferential financing, could be aligned with performance on these multidimensional metrics.

· Creating a Protective Ecosystem for Accountability: Robust, legally enforced protections for whistleblowers, investigative journalists, and anti-corruption officials are fundamental. This may include secure reporting channels, legal aid, and, where necessary, international relocation support for those under threat.

· Harnessing Technology for Inclusive Governance: Digital tools should be leveraged to deepen democracy. This includes secure platforms for citizen feedback on legislation, open-data portals for public spending, and digital civic assemblies that allow for informed deliberation on key national issues, complementing representative institutions.

Conclusion: The Collective Imperative for Renewal

Addressing leadership deficiencies is not a passive exercise but an active, continuous project of societal commitment. It requires the deliberate construction of systems that incentivize integrity and penalize malfeasance. For Nigeria, it is the arduous task of rebuilding a social contract through impartial institutions. For Africa, it is the strategic use of collective action to elevate governance standards continent-wide. For the world, it is the courageous redesign of international systems to foster genuine cooperation and justice. Ultimately, the quality of leadership is a direct reflection of the standards a society upholds and enforces. By implementing this multilayered framework—demanding accountability, rewarding merit, and empowering citizens—a new paradigm of leadership can emerge, transforming it from a recurrent source of crisis into the most reliable engine for human progress and shared prosperity.

Dr. Tolulope A. Adegoke, AMBP-UN is a globally recognized scholar-practitioner and thought leader at the nexus of security, governance, and strategic leadership. His mission is dedicated to advancing ethical governance, strategic human capital development, and resilient nation-building, and global peace. He can be reached via: tolulopeadegoke01@gmail.com, globalstageimpacts@gmail.com

Related

Opinion

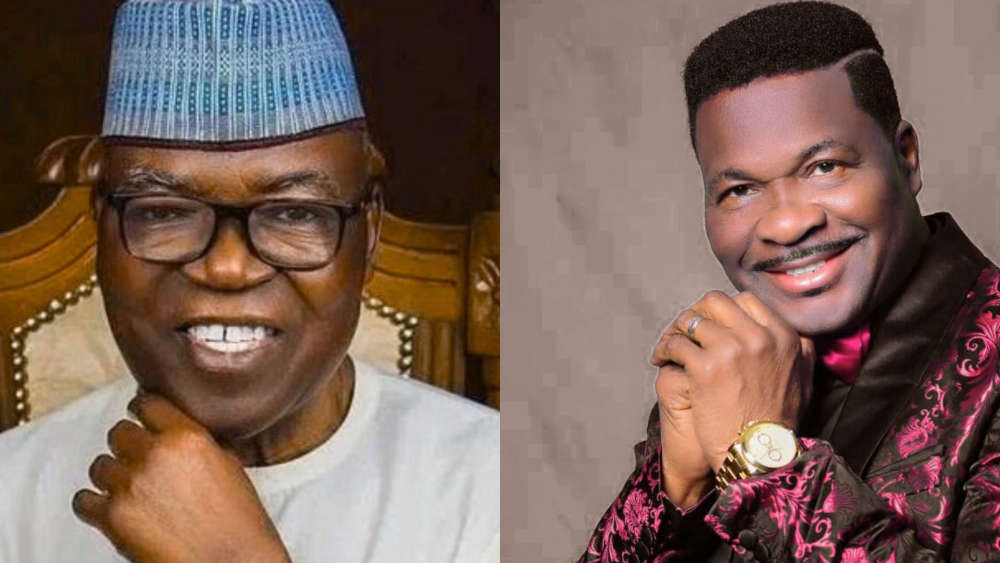

Tali Shani vs Mike Ozekhome: How a Legal Mole-Hill Was Turned into a Mountain

Published

1 day agoon

February 6, 2026By

Eric

By Abubakar D. Sani, Esq

INTRODUCTION

News of the decision of a British Tribunal in respect of a property situate in London, the UK’s capital, whose ownership was disputed has gained much publicity since it was delivered in the second week of September 2025. For legal reasons, the charges brought against prominent lawyer, Chief Mike Ozekhome, SAN, based on same is the most that can be said of it as no arraignment was made before Hon. Justice Kekemeke of the High court of the FCT, Abuja, sitting in Maitama.

Accordingly, this intervention will be limited to interrogating the common, but false belief (even in legal circles), that the Tribunal somehow indicted him with conclusive ‘guilt’. I intend to argue that this belief is not correct; and that, on the contrary, nothing could be further from the truth. For the sake of context, therefore, it is necessary to refer to relevant portions of the decision of Judge Paton (the name of the Tribunal’s presiding officer), which completely exonerated Chief Ozekhome, but which his detractors have always conveniently suppressed.

WHAT DID THE TRIBUNAL SAY?

Not a few naysayers, smart-alecs, emergency analysts and self-appointed pundits have been quick to latch on to some passages in the judgement of the Tribunal which disagreed with Ozekhome’s testimony to justify their crucifixion of Chief Ozekhome – even without hearing his side of the story or his version of events. This is a pity, of course, especially for the supposedly learned senior lawyers among them who, by ignoring the age-old principle of fair hearing famously captured as audi alterem partem (hear the other side) have unwittingly betrayed patent bias, malice, malevolence and utter lack of bona fides as the major, if not exclusive, motivator of their view-points and opinions. I have particularly watched about five of such senior lawyers shop from one platform to another, with malicious analysis to achieve nothing, but reputational damage. They know themselves.

Before proceeding to those portions, it is important to acknowledge that the Tribunal conducted a review of the evidence placed before it. The proceedings afforded all parties the opportunity to present their respective cases. The learned Judge carefully evaluated the testimonies, documentary exhibits and surrounding circumstances and rendered a reasoned decision based on the materials before the Tribunal.

It is also not in doubt that the Tribunal made certain critical observations in the course of assessing the credibility of the witnesses and the plausibility of their explanations. Such evaluative comments are a normal and inevitable feature of judicial fact-finding, particularly in property tribunals in contested proceedings involving complex transactions and disputed narratives. They do not amount to indictment.

It is precisely the improper isolation and mischaracterization of some of these observations that have given rise to the present misconception that the Tribunal somehow pronounced a verdict of guilt on Chief Ozekhome. It is therefore necessary to place the relevant excerpts in their proper legal and factual context, so as to demonstrate how the self-same tribunal exonerated Ozekhome.

“Paragraph 98: Once one steps back from that material, and considers the Respondent’s own direct personal knowledge of relevant matters relating to this property, this only commences in 2019. That is, he confirmed, when he was first introduced to Mr. Tali Shani – he thought in about January of that year. He did not therefore know him in 1993, or at any time before January 2019. He could not therefore have any direct knowledge of the circumstances of the purchase of this property, or its management prior to 2019. He had, however, known the late General Useni for over 20 years prior to his death, as both his lawyer and friend.

“Paragraph 103: Such of the Respondent’s written evidence had been about the very recent management of the property, and in particular his dispute over its management (and collection of rents) with one Nicholas Ekhorutowen, who provided no evidence in this case. The Respondent confirmed in oral evidence that it was upon the execution of the powers of attorney that he came into possession of the various pre registration title and conveyancing documents which formed part of his disclosure. These had been handed over to him by the next witness who gave evidence, Mr. Akeem Johnson.

“Paragraph 168: Unlike the fictitious “Ms. Tali Shani”, a man going by the name of Mr. Tali Shani exists and gave evidence before me in that name. A certified copy of an official Nigerian passport was produced both to the Land Registry and this Tribunal, stating that Mr. Tali Shani was born on 2nd April 1973. I do not have the evidence, or any sufficient basis, to find that this document – unlike the various poor and pitiful forgeries on the side of the “Applicant” – is forged, and I do not do so.

“Paragraph 200: First, I find that General Useni, since he was in truth the sole legal and beneficial owner of this property (albeit registered in a false name), must in some way have been connected to this transfer, and to have directed it. He was clearly close to, and on good terms with, the Respondent. There is no question of this being some sort of attempt by the Respondent to steal the general’s property without his knowledge.

“Paragraph 201: As to precisely why General Useni chose to direct this transfer to the Respondent, I do not need to (and indeed cannot) make detailed findings. I consider that it is highly possible that it was in satisfaction of some debt or favour owed. The Respondent initially angrily denied the allegation (made in the various statements filed on behalf of the “Applicant”) that this was a form of repayment of a loan of 54 million Naira made during the general’s unsuccessful election campaign. In his oral evidence, both he and his son then appeared to accept that the general had owed the Respondent some money, but that it had been fully paid off. The general himself, when asked about this, said that he “did not know how much money he owed” the Respondent.

“Paragraph 202: I do not, however, need to find precisely whether (and if so, how much) money was owed. The transfer may have been made out of friendship and generosity, or in recognition of some other service or favour. The one finding I do make, however, is that it was the decision of General Useni to transfer the property to the Respondent.”

It must be emphasised that even where a court finds that a witness has given inconsistent, fluctuating, or implausible testimony, as some have latched on, such a finding does not, without more, translate into civil or criminal liability. At best, it affects the weight and credibility to be attached to such evidence. It does not constitute proof of fraud, conspiracy, or criminal intent. See MANU v. STATE (2025) LPELR-81120(CA) and IKENNE vs. THE STATE (2018) LPELR-44695 (SC)

Notwithstanding the Tribunal’s engagement with the evidence, certain passages had been selectively extracted and sensationalised by critics. On the ipssisima verba (precise wordings) of the Tribunal, only the above paragraphs which are always suppressed clearly stand out in support of Chief Ozekhome’s case, as the others were more like opinions.

Some paragraphs in the judgement in particular, appear to have been carefully selected as “weapons” in Chief Ozekhome’s enemies’ armoury, as they are most bandied about in the public space. The assumption appears to be that such findings are conclusive of his guilt in a civil property dispute. This is unfortunate, as the presumption of innocence is the bedrock of our adversarial criminal jurisprudence. It is a fundamental right guaranteed under section 36 of the Constitution and Article 7 of the African Charter which, regrettably, appear to have been more observed in the breach in his case.

More fundamentally, the selective reliance on few passages that disagreed with his evidence or testimony and that of Mr. Tali Shani, ignore the above wider and more decisive findings of the Tribunal itself. A holistic reading of the judgment reveals that the Tribunal was far more concerned with exposing an elaborate scheme of impersonation, forgery, and deception orchestrated in the name of a fictitious Applicant, Ms Tali Shani, and not Mr. Tali Shani (Ozekhome’s witness), who is a living human being. These findings, which have been largely ignored in public discourse, demonstrate that the gravamen of the Tribunal’s decision lay not in any indictment of Chief Ozekhome, but in the collapse of a fraudulent claim against him, which was founded on false identity and fabricated documents.

The Tribunal carefully distinguished a fake “Ms” Tali Shani (the Applicant), who said she was General Useni’s mistress and owner of the property, and the real owner, Mr Tali Shani, who was Chief Ozekhome’s witness before the Tribunal. It was the Tribunal’s finding that she was nothing but a phantom creation and therefore rejected her false claim to the property (par. 123). It also rejected the evidence of her so called cousin (Anakwe Obasi) and purported son (Ayodele Obasi) (par. 124).

The Tribunal further found that it was the Applicant and her cohorts that engaged in diverse fraud with documents such as a fraudulent witness statement purportedly from General Useni; all alleged identity documents; fabricated medical correspondence; the statement of case and witness statements; a fake death certificate; and a purported burial notice. (Paragraph 125). Why are these people not concerned with Barrister Mohammed Edewor, Nicholas Ekhoromtomwen, Ayodele Damola, and Anakwe Obasi? Why mob-lynching Chief Ozekhome?

The Tribunal found that the proceedings amounted to an abuse of process and a deliberate attempt to pervert the course of justice. It therefore struck out the Applicant’s claim (Paragraphs 130–165). The Tribunal significantly found that Mr Tali Shani exists as a human being and had testified before it in June, 2024. It accepted a certified Nigerian passport he produced, and accepted its authenticity and validity (Paragraph 168). Can any objective person hold that Ozekhome forged any passport as widely reported by his haters when the maker exists?

Having examined the factual findings of the Tribunal and their proper context, the next critical issue is the legal status and probative value of such findings. The central question, therefore, is whether the observations and conclusions of a foreign tribunal, made in the course of civil proceedings, are sufficient in law to establish civil or criminal liability against a person in subsequent proceedings.

STATUS OF JUDGEMENTS UNDER THE LAW

The relevant statutory provisions in Nigeria are sections 59, 60, 61, 173 and 174 of the Evidence Act 2011, provide as follows, respectively:

Section 59: “The existence of any judgment, order or decree which by law prevents any court from taking cognisance of a suit or holding a trial, is a relevant fact, evidence of which is admissible when the question is whether such court ought to take cognisance of such suit or to hold such trial”;

Section 60(I): “A final judgment, order or decree of a competent court, in the exercise of probate. Matrimonial, admiralty or insolvency jurisdiction, which confers upon or takes away from any person any legal character. or which declares any person to be entitled to any such character or to be entitled to any specific thing, not as against any specified person but absolutely, is admissible when the existence of any such legal character, or the title of any such legal persons to an) such thing, is relevant (2) Such judgment, order or decree is conclusive proof (a)that any legal character which it confers accrued at the time when such judgment, order or decree came into operation; (b) that any legal character. to which it declares any such person to be entitled. accrued to that person at the time when such judgment order or decree declares it to have accrued to that person; (c) that any legal character which it takes away from any such person ceased at the time from which such judgment, order or decree declared that it had ceased or should cease; and (d) that anything to which it declares any person to be so entitled was the property of that person at the time from which such judgment. order or decree declares that it had been or should be his property”;

Section 61: “Judgments, orders or decrees other than those mentioned in section 60 are admissible if they relate to matters of a public nature relevant to the inquiry; but such judgments, orders or decrees are not conclusive proof of that which they state”

Section 173: “Every judgment is conclusive proof, as against parties and privies. of facts directly in issue in the case, actually decided by the court. and appearing from the judgment itself to be the ground on which it was based; unless evidence was admitted in the action in which the judgment was delivered which is excluded in the action in which that judgment is intended to be proved”.;

Section 174(1): “If a judgment is not pleaded by way of estoppel it is as between parties and privies deemed to be a relevant fact, whenever any matter, which was or might have been decided in the action in which it was given, is in issue, or is deemed to be relevant to the issue in any subsequent proceeding”;

(2):”Such judgment is conclusive proof of the facts which it decides, or might have decided, if the party who gives evidence of it had no opportunity of pleading it as an estoppel”.

It can be seen that the decision of the Tribunal falls under the purview of section 61 of the Evidence Act, as the provisions of sections 59 and 60 and of sections 173 and 174 thereof, are clearly inapplicable to it. In other words, even though some Judge Paton’s findings in respect of Chief Ozekhome’s testimony at the Tribunal relate to matters of public nature (i.e., the provenance and status of No. 79 Randall Avenue, Neasden, London, U.K and the validity of his application for its transfer to him) none of those comments or even findings is in any way conclusive of whatever they may assert or state (to use the language of section 60 of the Evidence Act).

In this regard, see the case of DIKE V NZEKA (1986) 4 NWLR pt.34 pg. 144 @ 159 where the Supreme Court construed similar provisions in section 51 of the old Evidence Act, 1948. I agree with Tar Hon, SAN (S. T. Hon’s Law of Evidence in Nigeria, 3rd edition, page 1041) that the phrase ‘public nature’ in the provision is satisfied where the judgement is clearly one in rem as opposed to in personam. It is pertinent to say a few words about both concepts, as they differ widely in terms of scope. The former determines the legal status of property, a person, a particular subject matter, or object, against the whole world, and is binding on all persons, whether they were parties to the suit or not. See OGBORU V IBORI (2005) 13 NWLR pt. 942 pg. 319 @407-408 per I. T. Muhammed, JCA (as he then was).

This was amplified by the apex court in OGBORU V UDUAGHAN (2012) LLJR -SC, where it held, per Adekeye, JSC that: “A judgment in rem maybe defined as the judgment of a court of competent jurisdiction determining the status of a person or thing as distinct from the particular interest of a party to the litigation. Apart from the application of the term to persons, it must affect the “res” in the way of condemnation forfeiture, declaration, status or title”.

By contrast, “Judgments ‘in personam’ or ‘inter partes’, as the name suggests, are those which determine the rights of parties as between one another to or in the subject matter in dispute, whether it be corporeal property of any kind whatever or a liquidated or unliquidated demand but which do not affect the status of either things or persons or make any disposition of property or declare or determine any interest in it except as between the parties (to the litigation). See HOYSTEAD V TAXATION COMMISSIONERS (1926) A. C. 155. These include all judgments which are not judgments in rem. None of such judgments at all affects any interest which third parties may have in the subject matter. As judgment inter partes, though binding between the parties and their privies, they do not affect the rights of third parties. See CASTRIQUE V IMRIE 141 E. R. 1062; (1870) L. R. 4H. L. 414”.

Suffice it to say that the decision of the London Property Tribunal was, in substance, one affecting proprietary rights in rem, in the sense that it determined the status and registrability of the property in dispute. However, it did not determine any civil or criminal liability, nor did it pronounce on the personal culpability of any party. The implication of this is that, even though the decision was in respect of a matter of a public nature, it was, nonetheless, not conclusive as far as proof of the status of the property, or – more importantly – Chief Ozekhome’s role in relation to it. Indeed, the property involved was not held to have been traced to the owner (General Useni) as having ever tried or convicted for owning same. I submit that the foregoing is the best case scenario in terms of the value of Judge Paton’s said decision, because under section 62 of the Evidence Act, (depending, of course, on its construction), it will fare even worse, as it provides that judgments “other than those mentioned in sections 59. 60 and 61 are inadmissible unless the judgment, etc is a fact in issue or is admissible under some other provision of this or any other Act”.

CONCLUSION

Some people’s usual proclivity to rush to judgment and condemn unheard any person (especially a high profile figure like Chief Ozekhome), has exposed him to the worst kind of unfair pedestrian analysis, malice, mud-slinging and outright name-calling especially by those who, by virtue of their training, ought to know better, and, therefore, be more circumspect, restrained and guarded in their utterances. This is all the more so because, no court of competent jurisdiction has tried or pronounced him guilty. It is quite unfortunate how some select lawyers are baying for his blood.

The decision of the London Tribunal remains what it is: a civil determination on attempted transfer of a property based on the evidence before it. It is not, and cannot be, a substitute for civil or criminal adjudication by a competent court. The presumption of innocence under Nigerian laws remains inviolable. Any attempt by commentators to usurp that judicial function through premature verdicts is not only improper, but inimical to the fair administration of justice.

Related

Opinion

The Atiku Effect: Why Tinubu’s One-Party Dream Will Never Translate to Votes in 2027

Published

2 days agoon

February 5, 2026By

Eric

By Dr. Sani Sa’idu Baba

It is deeply disappointing if not troubling to watch a former governor like Donald Duke accuse Atiku Abubakar of contesting for the presidency “since 1992” without identifying a single provision of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria that such ambition violates. Donald Duke was once widely regarded as one of the most intelligent and forward-thinking leaders of his generation, which makes it even more puzzling to understand what must have come over him to suddenly align with those throwing tantrums at others who are by far more competent, experienced, and eligible than themselves. While I acknowledge that Duke has recently moved to the ADC, the party that Atiku belongs to, Nigerians should not be distracted by his kind of rhetoric.

As former presidential candidate and ADC chieftain Chief Dele Momodu has repeatedly stated, “everyone is afraid of Atiku Abubakar,” particularly as the 2027 presidential election approaches. That fear, according to Momodu, explains the ongoing campaign of calumny against him. Donald Duke’s remarks therefore cannot be separated from this wider effort to diminish a man widely seen as the most formidable opposition figure in Nigeria today.

However, the issue of Donald Duke is not the central purpose of my message today. It is only incidental. The real purpose is to share what should be considered good news for Nigerians, the growing perception among ordinary citizens and the conversations happening daily at junctions, gatherings, markets, campuses, mosques, churches, and in the nooks and crannies of the country. The truth is that Nigerians are largely unbothered by the APC’s one-party state ambition. They are not impressed by forced defections or elite political gymnastics. What occupies their minds instead is the unrelenting presence of opposition, sustained hope, and the quiet but powerful confidence inspired by what has now become known as the “Atiku Effect”.

In my own opinion, which aligns with the thinking of many discerning Nigerians, no one in either the opposition or the ruling camps today appears healthier physically, mentally, socially and politically than Atiku Abubakar. Health is not determined by propaganda or ageism, but by function, resilience, and capacity. As we were taught in medical school, “healthspan, not lifespan, defines vitality,” and “physiological resilience is age-independent.” These principles make it clear that fitness, clarity of thought, stamina, cognitive and physiological reserve matter far more than the number of years lived. By every observable measure, Atiku remains fitter and more grounded than many who are younger but visibly exhausted by power.

It is no longer news that Nigeria is being pushed toward a one-party state through the coercion of opposition governors into the ruling APC. What is increasingly clear, however, is that this strategy reflects anxiety rather than strength. Nigerians understand that governors do not vote on behalf of the people, and defections do not automatically translate into electoral victory. This same script was played before, and history has shown that elite alignment cannot override popular sentiment. Just as it happened in 2015, decamping governors cannot save a sitting president when the people have already reached a conclusion.

This is where the Atiku Effect becomes decisive. Atiku Abubakar represents continuity of opposition, courage in the face of intimidation, and the refusal to surrender democratic space. His consistency reassures Nigerians that democracy is still alive and that power can still be questioned. This is precisely why Dele Momodu’s assertion that “everyone is afraid of Atiku Abubakar” resonates so strongly across the country. It is not fear of noise or recklessness, but fear of discipline, experience, and endurance.

Across Nigeria today, the ruling party is increasingly treated as the most unserious political party in the history of Nigeria, not because it lacks power, but because it lacks credibility. Nigerians know that hunger does not disappear because governors defect, inflation does not bow to propaganda, and hardship does not respond to political coercion. What they see instead is a widening gap between political theatrics and lived reality. In that gap stands Atiku Abubakar, a constant reminder that an alternative voice still exists and that the idea of a one-party state cannot survive where hope remains alive.

Let me say this unapologetically: the one-party project being pursued by the ruling party is dead on arrival. It is dead because Nigerians are politically conscious. It is dead because votes do not move with defections. And above all, it is dead because Atiku Abubakar remains standing, indefatigable, resilient, and central to the national conversation. As long as he continues to challenge bad governance and embody opposition, democracy in Nigeria will continue to breathe. And that, more than anything else, explains why so many are desperately trying and failing to stop him because Atiku Abubakar is a phenomenon and a force that cannot be stopped in 2027…

Dr. Sani Sa’idu Baba writes from Kano, and can be reached via drssbaba@yahoo.com

Related

Adding Value: Be Intentional in Carrying Your Cross by Henry Ukazu

APC Drops Uzodinma As National Convention Chairman, Names Masari As Replacement

A Holistic Framework for Addressing Leadership Deficiencies in Nigeria, Others

Daredevil Smugglers Kill Customs Officer in Ogun

Tali Shani vs Mike Ozekhome: How a Legal Mole-Hill Was Turned into a Mountain

Glo Boosts Lagos Security with N1bn Donation to LSSTF

Friday Sermon: Facing Ramadan: A Journey Through Time 1

Ghana 2028: Mahamudu Bawumia Claims NPP’s Presidential Ticket

Senate Passes Electoral Bill 2026, Rejects Real-time Electronic Transmission of Results

Fight Against Terrorism: US Troops Finally Arrive in Nigeria

Legendary Gospel Singer, Ron Kenoly, is Dead

Glo Leads in Investments, Performance As NCC Sets New Standard for Telecoms

Wike Remains Undisputed Rivers APC, PDP Leader, Tinubu Rules

Memoir: My Incredible 10 Years Sojourn at Ovation by Eric Elezuo

Trending

-

Boss Of The Week6 days ago

Boss Of The Week6 days agoGhana 2028: Mahamudu Bawumia Claims NPP’s Presidential Ticket

-

Headline2 days ago

Headline2 days agoSenate Passes Electoral Bill 2026, Rejects Real-time Electronic Transmission of Results

-

National3 days ago

National3 days agoFight Against Terrorism: US Troops Finally Arrive in Nigeria

-

Featured4 days ago

Featured4 days agoLegendary Gospel Singer, Ron Kenoly, is Dead

-

National6 days ago

National6 days agoGlo Leads in Investments, Performance As NCC Sets New Standard for Telecoms

-

Headline4 days ago

Headline4 days agoWike Remains Undisputed Rivers APC, PDP Leader, Tinubu Rules

-

Featured6 days ago

Featured6 days agoMemoir: My Incredible 10 Years Sojourn at Ovation by Eric Elezuo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCourt Restrains NLC, TUC from Embarking on Strike, Protest in Abuja