Boss Picks

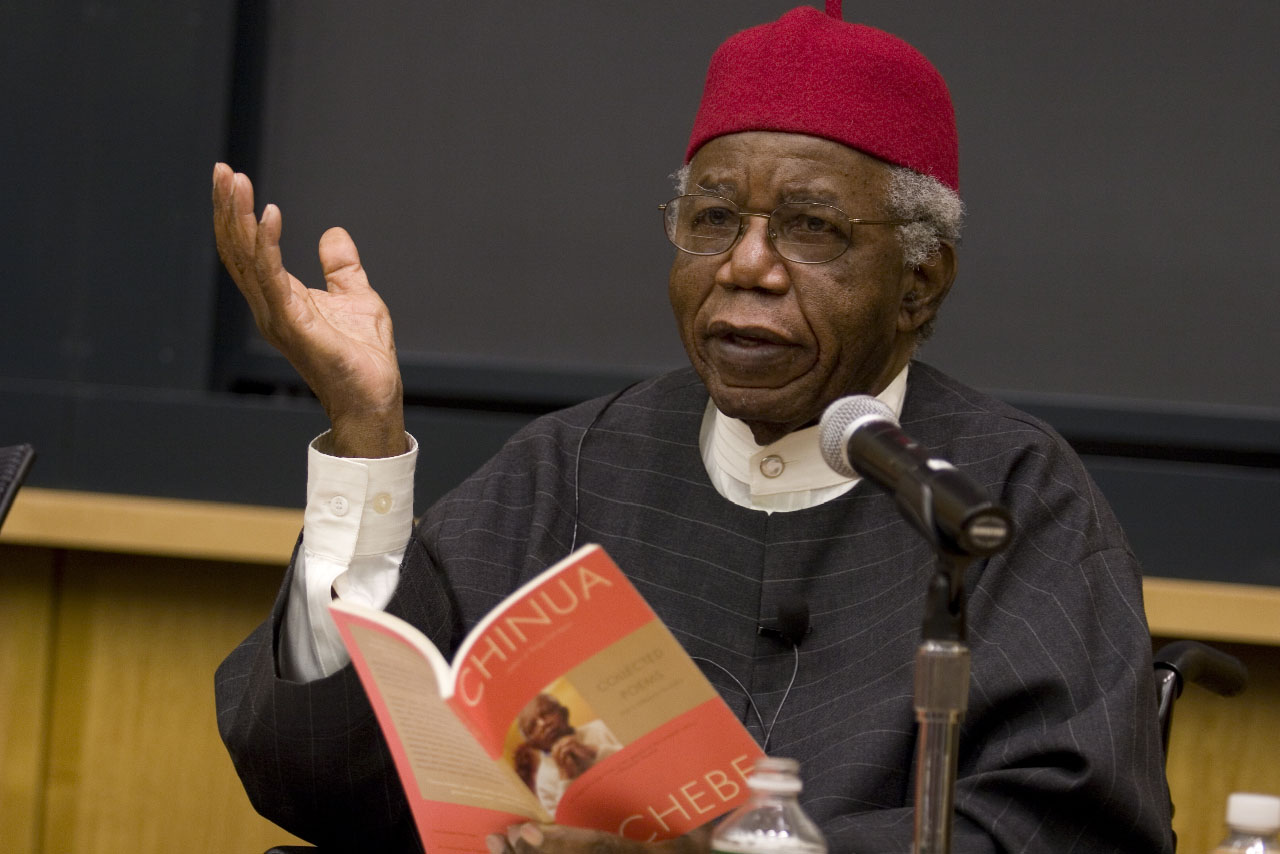

Garlands for Prolific Writer, Chinua Achebe, on 94th Posthumous Birthday

Published

1 year agoon

By

Eric

By Eric Elezuo

Writers never die is one expression that aptly describes the immortality of the life and work of one of the world’s leading and prolific writers, teacher and profound nationalist, Chinua Achebe.

A dogged fighter, stubborn to his beliefs of an egalitarian society, and a deep adherence to culture and traditions of the African people, with special bias to his Igbo roots, Achebe lived his 83 years on earth, ensuring that no one, who lives near a river, washes his hands with spittle. His vocal and actionable condemnation of the wrongs of colonialism transcended to post colonial Nigeria, where he continued the advocacy for a just and free society, founded on equity and equality. He never reneged on his strong rebuke against corruption till he breathe his last on that fateful day in March, 2013, in Boston, Massachusetts, in the United States of America.

Perhaps, one could attribute the greatness of Chinua Achebe, as he was simply known, to quite a number of factors, most of which appears ornately abstract.

His ability to discern at an early stage his true calling, which was purely artistic and literary, prompting him to jettison an attractive opportunity to become a doctor. It is worth knowing that Achebe was admitted into the now University of Ibadan as pioneer students to study Medicine on a scholarship. However, his discovery of the way foreign authors, especially European authors described Africa, roused the nationalism in him, and prompted him to make a radical and risky change to the Humanities. The risk was enormous, but his stubborn adherence to his principles, ensured he never looked back. He lost the scholarship on that decision, and had to struggle through school though not without little support of the government as well as his brother. Looking back, his choice paid off handsomely.

Again, kudos should be given to the likes of Albert Schweitzer and Joseph Conrad, both of whom Achebe described as “a thoroughgoing racist, and Joyce Cary, who wrote Mr Johnson, for their contributions to greatness of Achebe, though unknowingly. It was Conrad’s book, Heart of Darkness, which gave Africa and Africans a completely negative description, that warranted a necessity to do a rejoinder. He decision to tell a better narrative to correct the lopsided impression of the black race led to his interest in Literature, and finally to writing and release of the world renowned epic, Things Fall Apart, in 1957.

The Igbo culture of Storytelling also impacted Achebe’s glory. The act was a mainstay of the Igbo tradition and an integral part of the community. Wikipedia wrote that Achebe’s mother and his sister, Zinobia, told him many stories as a child, which he repeatedly requested. It was here he got most of his storyline and sharpened his storytelling acumen.

We can also give kudos to the collages his father hung on the walls of their home, as well as almanacs and numerous books—including a prose adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (c. 1590) and an Igbo version of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). They play parts in honing his writing interest, and most of them were later recreate in his novels and stories, especially ceremonies of Igbo origins.

Though the Things Fall Apart is not Achebe’s first in the analysis of his writings, it broke all protocol, re-addressed biased impression, and tends to release Africa from chain of a dark continent description. Achebe made his mark with his first outing as a writer thereby fulfilling a destiny, he drafted for himself. Since then, he never looked back, churning out classics after classics that remodeled world literature, at least from the perspective of the average African man. It was therefore, for love of action and tangibility that he opposed negritude, preferring tigritude in its stead. His argument, as he put on paper says “A tiger doesn’t proclaim its tigerness; it jumps on its prey.” He wanted African writers to show the stuff they are made of rather than verbalize it.

Principled and well brought up, Achebe on many occasions, rejected national honours, saying there was actually no reason to allow himself be honoured by a corrupt society.

Today, 11 years after his death and 67 years after the publication of the blockbuster Things Fall Apart, Achebe’s image continues to loom large, remain larger than life and covering the literary world like a colossus, as well as giving Africans the pride that they so much deserve.

THE MAN CHINUA ACHEBE

Born Albert Chinụalụmọgụ Achebe on November 16 1930, sharing same birthday date with Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Achebe lived his entire conquering the fields of literature in every ramification. He was a novelist, poet, and critic who is regarded as a central figure of modern African literature.

He hails from Ogidi, in Anambra State, and born to a teacher-evangelist father, Isaiah Okafo Achebe, while his mother, Janet Anaenechi Iloegbunam, was church leader, farmer and daughter of a blacksmith from Awka.

Achebe grew side by side with his five other siblings; four boys and a girl. They were Frank Okwuofu, John Chukwuemeka Ifeanyichukwu, Zinobia Uzoma, Augustine Ndubisi, and Grace Nwanneka.

Achebe’s childhood was greatly influenced by both Igbo traditional culture and postcolonial Christianity, both of which he allowed to exist side by side all through his life.

Records have it that he excelled while pursuing his academic career. It was while attending what is now the University of Ibadan, that his antenna of fierce criticiam of how Western literature depicted Africa, became sharpened.

Achebe’s educational pursuit started in 1936, when he entered St Philips’ Central School in the Akpakaogwe region of Ogidi for his primary education. He was later moved to a higher class when the school’s chaplain took note of his intelligence. He showcased his brilliance from the very beginning.

“One teacher described him as the student with the best handwriting and the best reading skills in his class.”

After primary education, Achebe moved to the prestigious Government College Umuahia, in present-day Abia State, for his secondary education. He combined his formal education pursuit with attendance of Sunday school every week and the special services held monthly.

Achebe later in 1942 enrolled in Nekede Central School, outside of Owerri, and was reported to be ‘particularly studious and passed the entrance examinations for two colleges.’

He moved to Lagos after graduation, and worked for the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS), garnering international attention for his 1958 novel Things Fall Apart. In less than 10 years he would publish four further novels through the publisher Heinemann, with whom he began the Heinemann African Writers Series and galvanized the careers of African writers, such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Flora Nwapa.

His first novel, described widely as his magnum opus, Things Fall Apart (1958), occupies a pivotal place in African literature and remains the most widely studied, translated, and read African novel. Along with Things Fall Apart, his No Longer at Ease (1960) and Arrow of God (1964) complete the “African Trilogy”.

Later novels include A Man of the People (1966) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987). In the West, Achebe is often referred (or recognized as) to as the “father of African literature”, although in his humility, he had at various times, vigorously rejected the characterization.

Achebe’s interest in writing was natured when he sought to escape the colonial perspective that framed African literature at the time, and drew from the traditions of the Igbo people, Christian influences, and the clash of Western and African values to create a uniquely African voice. He wrote in and defended the use of English, describing it as a means to reach a broad audience, particularly readers of colonial nations.

When the region of Biafra broke away from Nigeria in 1967, Achebe supported Biafran independence and acted as ambassador for the people of the movement appealing to the people of Europe and the Americas for aid. Though he engaged in politics at the fall of Biafra in 1970, he quickly exited as he became disillusioned over the continuous corruption and elitism he witnessed.

He lived in the United States for several years in the 1970s, and returned to the US in 1990 after a car crash left him partially paralyzed. He stayed in the US in a nineteen-year tenure at Bard College as a professor of languages and literature.

Winning the 2007 Man Booker International Prize, from 2009 until his death he was Professor of African Studies at Brown University. Achebe’s work has been extensively analyzed and a vast body of scholarly work discussing it has arisen. In addition to his seminal novels,

Achebe’s oeuvre includes numerous short stories, poetry, essays and children’s books. A titled Igbo chief himself, his style relies heavily on the Igbo oral tradition, and combines straightforward narration with representations of folk stories, proverbs, and oratory. Among the many themes his works cover are culture and colonialism, masculinity and femininity, politics, and history. His legacy is celebrated annually at the Chinua Achebe Literary Festival.

Achebe’s debut as an author was in 1950 when he wrote a piece for the University Herald, the university’s magazine, entitled “Polar Undergraduate”. It used irony and humour to celebrate the intellectual vigour of his classmates. He followed with other essays and letters about philosophy and freedom in academia, some of which were published in another campus magazine called The Bug. He served as the Herald‘s editor during the 1951–52 school year. He wrote his first short story that year, “In a Village Church” (1951), an amusing look at the Igbo synthesis between life in rural Nigeria with Christian institutions and icons. Other short stories he wrote during his time at Ibadan—including “The Old Order in Conflict with the New” (1952) and “Dead Men’s Path” (1953)—examine conflicts between tradition and modernity, with an eye toward dialogue and understanding on both sides. When the professor Geoffrey Parrinder arrived at the university to teach comparative religion, Achebe began to explore the fields of Christian history and African traditional religions.

After the final examinations at Ibadan in year 1953, Achebe was awarded a second-class degree. Rattled by not receiving the highest level, he was uncertain how to proceed after graduation and returned to his hometown of Ogidi. While pondering possible career paths, Achebe was visited by a friend from the university, who convinced him to apply for an English teaching position at the Merchants of Light school at Oba. It was a ramshackle institution with a crumbling infrastructure and a meagre library; the school was built on what the residents called “bad bush”—a section of land thought to be tainted by unfriendly spirits. It was from this ‘bad bush’ that Achebe kickstarted his career path before trying out other avenues until the Nigeria/Biafra War broke out.

Achebe returned with his family to Ogidi, at the fall of Biafra in 1970 to discover their home destroyed. He then took up a job at the University of Nigeria in Nsukka and immersed himself once again in academia. He was unable to accept invitations to other countries, however, because the Nigerian government revoked his passport due to his support for Biafra.

In the last 12 years of his life, Achebe devoted his time more academic pursuit and writings, and winning more laurels.

In 2000 he published Home and Exile, a semi-biographical collection of both his thoughts on life away from Nigeria, as well as discussion of the emerging school of Native American literature.

In October 2005, the London Financial Times reported that Achebe was planning to write a novella for the Canongate Myth Series, a series of short novels in which ancient myths from myriad cultures are reimagined and rewritten by contemporary authors.

Achebe was awarded the Man Booker International Prize in June 2007. The award helped correct what “many perceived as a great injustice to African literature, that the founding father of African literature had not won some of the key international prizes.”

For the International Festival of Igbo culture, Achebe briefly returned to Nigeria to give the Ahajioku Lecture. Later that year he published The Education of A British-Protected Child, a collection of essays. In autumn he joined the Brown University faculty as the David and Marianna Fisher University Professor of Africana Studies.

In 2010, Achebe was awarded The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize for $300,000, one of the richest prizes for the arts.

In 2012, Achebe published There Was a Country: A Personal History of Biafra. The work re-opened the discussion about the Nigerian Civil War. It would be his last publication during his lifetime; Achebe died after a short illness on 21 March 2013 in Boston, United States. He was buried in his hometown of Ogidi.

Achebe, there was indeed a man! And on this 94th Posthumous birthday, the world raises a toast.

Related

You may like

Boss Picks

Aesthetics, Landscape, Professionalism: You Can’t See ABUAD in One Day!

Published

7 days agoon

February 15, 2026By

Eric

By Eric Elezuo

The idea behind one of Nigeria’s elevated private higher institution of learning, the Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti (ABUAD) is not only humongous, but filled with classy intentions, beautiful landscape, and professionalism in tutelage and character molding.

A visit to this great citadel of learning is not a one day affair, cause no one can see ABUAD in One day; not even in one week, one month or a year, as this reporter can attest to. ABUAD is huge. ABUAD is large. ABUAD is an institution beyond the literary definition. ABUAD is a dream projected to last a lifetime, and it has not failed to live up to billing.

Navigating through the bustling streets of Ado-Ekiti via the centre of Ekiti Parapo Arena, and into the gracious Olusegun Obasanjo Way enroute Aye Ekiti, the institution is situated at an altitude of over 1,500 feet, and located on a 130-hectare piece of land; large enough to birth a kingdom, and accommodate whatever facility dreamt of.

The Boss learnt that the institution was established to address the mismatch between academic programmes and the demands of the labour market in Nigeria.

Established in 2009, in Ado-Ekiti, the capital of Ekiti State, by a distinguished legal icon, academic pillar and seasoned entrepreneur, Prof Afe Babalola, ABUAD has distinguished itself as a force to reckon with in the fields of research and training, developing and churning out creative minds, who have constituting a megaforce in global development.

By the benefit of hindsight, the University offers Academic programmes in seven Colleges: Sciences, Law, Engineering, Social and Management Sciences, Medicine and Health Sciences, Pharmacy and Postgraduate Studies. Beyond the academic ratings, ABUAD boasts of the very best of facilities for health, recreation, environmental, electricity, agriculture and more. It is also a centre of academic discipline with academic and non-academic staff of repute, whose stock-in-trade remain the production of all-round, well-tutored and easy-to-fit personality.

The institution is managed by the Vice Chancellor, Prof Smaranda Olarinde, which academic and administrative catalogue is quiet envious to behold.

By every standard, the institution merits its Time Higher Education (THE) Impact ranking as at 2025 as the 84th in the world, 3rd in Africa and 1st in Nigeria. Great feat!

The Engineering College, one of the foremost architectural intelligence on the ABUAD land, is built on three and half acres of land, and is reputed to be one of the largest in Africa. The college was inaugurated by former President Goodluck Jonathan.

Campuses

Admission requirement

The admission requirement for the school varies between the different colleges. However, as with all Nigerian universities, for undergraduate programs the candidate is required to have at least 5 credits in subjects such as mathematics, English language and any other three subjects that are relevant to the course of study. The student is required to have passed the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board JAMB Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination (UTME), after which the candidate is expected to take an oral interview with an academic staff of the prospective college before admission can be given. The university also offers direct entry admission to students who wish to transfer from another university or have undergone either an Advanced Level program or a degree foundation program. The level at which they are admitted into is decided by the college and varies among them.

Undergraduate colleges

The university operates a collegiate system and has six major colleges. They are the College of Engineering, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, College of Sciences, College of Law, College of Social and Management Sciences, and College of Pharmacy. Some of the colleges offer post graduate programme in some departments.

The College of Law

The College of Law is fully accredited by the National University Commission (NUC) of Nigeria. The college consists of fully furnished classrooms, a common room, a library containing law journals and articles, and a moot court for students to have court practice sessions. There are a number of student chambers in the college backed by a staff mentor who battle against each other in moot court sessions. Associate Prof. Elisabeta Smaranda Olarinde (FCAI) is the pioneer provost of the college of Law and is still the current provost of the college; she is also the acting vice chancellor of the university. The College of Law, which is regarded as one of the best law colleges in Nigeria, offers both undergraduate and post-graduate degrees (master’s level) in law.

The College of Engineering

The college of engineering was accredited by both the NUC and COREN during their one-week visit to the college. The main engineering building which houses laboratories, a central engineering library, lecturer rooms, an auditorium, a central engineering workshop and a certified Festo training center. The engineering building is named after the former Nigerian president Dr. Goodluck Jonathan and was commissioned by him on 20 October 2013 during the university’s first convocation ceremony. Prof. Israel Esan Owolabi served as the pioneer provost of the college of engineering; he stepped down from the post in 2015 and he is currently engaged in teaching activities in the electrical/electronics engineering programme.

Academic programs

- B.Eng. Mechanical Engineering

- B.Eng. Mechatronic Engineering

- B.Eng. Electrical/Electronic Engineering

- B.Eng. Petroleum Engineering

- B.Eng. Civil Engineering

- B.Eng. Chemical Engineering

- B.Eng. Computer Engineering

- B.Eng. Agricultural Engineering

- B.Eng. Biomedical Engineering

- B.Eng. Aeronautical and Astronautical Engineering

The College of Sciences

The College of Sciences is one of the pioneer colleges of the university after the university’s approval by the Nigerian University Commission (NUC). The university admitted students at inception on 4 January 2010.

Academic programs

- B.Sc. Microbiology

- B.Sc. Human Biology

- B.Sc. Biotechnology

- B.Sc. Biochemistry

- B.Sc. Chemistry

- B.Sc. Industrial Chemistry

- B.Sc. Computer Science

- B.Sc. Geology.

- B.Sc. Physics with Electronics

- B.Sc. Physics

- B.Sc. Petroleum Chemistry

- B.Arch Architecture

The College of Social and Management Sciences

At inception, on 4 January 2010 the university admitted students into the College of Social and Management Sciences, being one of the pioneer colleges of the university. The session ran smoothly without hitches from 4 January to August 2010. The second session of the university started on October 4, 2010, with over 1,000 students. So far the, university has maintained strict compliance with its academic calendar which makes it possible for students to pre-determine their possible date of completion of their programmes even before enrolment. It has been the policy of the university to post on-line students’ results within 24hours of approval by the Senate.

Academic programs

- B.Sc. Economics

- B.Sc. Accounting

- B.Sc. Banking and Finance

- B.Sc. Business Administration

- B.Sc. Tourism and Events Management.

- B.Sc. Political Science

- B.Sc. International Relations and Diplomacy

- B.Sc. Peace and Conflict Studies

- B.Sc. Intelligence and Security Studies

- B.Sc. Social Justice

- B.Sc. Communication and Media Studies

- B.Sc. Marketing

- B.Sc. Entrepreneurship

- B.Sc. Sociology

The College of Medicine and Health Sciences

The college commenced activities in October 2011 having been approved by National Universities Commission.

Academic programs

- Medicine and Surgery (M.B.B.S)

- B.NSc. Nursing Sciences

- B.MLS. Medical Laboratory Science

- B.Sc. Anatomy

- B.Sc. Physiology

- B.Sc. Human Nutrition and Dietetics

- B.Sc. Pharmacology

- B.Sc. Public Health

- Pharm.D Pharmacy

- B.DS. Dentistry

- OD. Optometry

The College of Arts and Humanities

Academic programs

- B. A. Performing Arts

- B. A. English

- B. A. History and International Studies

- B. A. Linguistics

The College of Agriculture

Academic programs

- B. Agric. Animal Science

- B. Agric. Agricultural Economics

- B. Agric. Extension Education

- B. Agric. Crop Science

- B. Agric. Soil Science

Postgraduate college

The university operates a collegiate system and has five major Postgraduate colleges. They are the College of Engineering, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, College of Sciences, College of Law and College of Social and Management Sciences.

ABUAD INDEPENDENT POWER PROJECT

To harness thorough academic and character building, the institution is operated off the national grid as it is run on its own power project, with a dam that powers its electrical needs.

HEALTH AND AGRICULTURE

ABUAD operates of the best medical schools and facilities in the country as it boasts of almost all equipment, space and atmosphere for sundry medical conditions, with reputable medical personnel to complement the environment.

In the vein, the institution runs a developed farming culture, that accommodates rearing of livestock and production of cash and food crops.

The farm sits on a large expanse of loamy soil, complimented with consistent flow of irrigation and drainage, and maintained with the classic of horticulture. The settlement is run by a team of professionals made up of Agroeconomists, horticulturist and more.

It is also worth knowing that the school has its Cassava Processing Factory just as it operates a self sustaining Carbonated Drink Factory.

ABUAD practically offers everything!

ABUAD’S FOUNDER, AARE AFE BABALOLA

Born in 1929, Aare Afe Babalola SAN is one of the most distinguished legal luminaries of his generation, renowned both in Africa and globally for his profound contributions to the legal profession and the advancement of education. With over five decades of uninterrupted legal practice, Aare Babalola’s career is a testament to exceptional dedication, strategic advocacy, and visionary leadership.

A highly accomplished advocate, he has led some of the most celebrated cases in Nigerian legal history, representing high-profile clients, including government institutions, multinational corporations, and individuals. His advocacy spans domestic and international courts, including contributions as a consultant to the Federal Government of Nigeria, World Bank, and various conglomerates. His extensive experience includes his role in arbitration, both locally and internationally, where he remains a respected authority. Aare Babalola has appeared in numerous landmark cases, shaping Nigerian jurisprudence and establishing himself as one of the nation’s most formidable legal minds.

His influence goes beyond the courtroom. As the Founder of Afe Babalola & Co. (Emmanuel Chambers), one of Nigeria’s leading law firms, Aare Babalola has trained over 300 lawyers, including 14 Senior Advocates of Nigeria (SANs), judges, and attorneys-general, making his chambers one of the most significant contributors to the legal profession in Nigeria. His exceptional litigation skills and legal acumen earned him the prestigious title of Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) in 1987, cementing his place at the pinnacle of legal practice in the country.

A renowned scholar and author, Aare Babalola has authored several authoritative legal texts, including Injunctions and Enforcement of Orders and Law and Practice of Evidence in Nigeria. His contributions to legal education extend to teaching at the Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies and delivering lectures at prestigious universities such as the University of Lagos and the University of Ibadan. His popular column, YOU AND THE LAW, published in the Nigerian Tribune, reflects his commitment to educating the public on legal matters.

Beyond his legal practice, Aare Babalola has made extraordinary strides in education. His experience as Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council of the University of Lagos (2001-2007) exposed him to the declining standards of education in Nigeria, spurring him to establish Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti (ABUAD).

ABUAD has quickly become a beacon of academic excellence, setting new standards in Nigeria’s educational system. His efforts in education have been recognized globally, with numerous honorary degrees from universities, including the University of London, University of Lagos, and Ekiti State University.

Aare Babalola’s leadership in academia and law has earned him numerous accolades, including the Officer of the Federal Republic (OFR), Commander of the Order of the Niger (CON), and international recognition such as the Queen Victoria Commemorative Award at the Socrates Awards in Oxford, UK. He was named Africa Man of the Year on Food Security and awarded an Honorary Doctor of Management by the Federal University of Technology, Akure. His groundbreaking achievements continue to inspire generations of lawyers and leaders across Africa and beyond.

In addition to his legal and educational contributions, Aare Babalola remains a committed philanthropist and advocate for reform in various sectors. His vast experience, unmatched expertise, and unwavering commitment to excellence make him not only a legal icon but also a trailblazer in the fight for quality education and justice.

Key Achievements:

- Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN), 1987.

- Officer of the Federal Republic (OFR).

- Commander of the Order of the Niger (CON).

- Pro-Chancellor and Chairman of the Governing Council, University of Lagos (2001-2007).

- Founder and Chancellor, Afe Babalola University, Ado-Ekiti (ABUAD).

- Queen Victoria Commemorative Award winner, Oxford UK.

- Fellow, Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies.

- Honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of London, Ekiti State University, University of Lagos, and more

ABUAD is a legacy, just like its Founder, Afe Babalola SAN.

Photos: Ben Osei and Ken Ehimen

Related

Boss Picks

Emmanuel ‘Nuel’ Ojei: The Untold Story of the Unassuming Billionaire

Published

4 weeks agoon

January 26, 2026By

Eric

By Eric Elezuo

The name Nuel Ojei rings a bell loud enough for even the deaf to hear. His Exploits were manifold, unprecedented and humongous. He was a man of extreme means, a philanthropist of the superlative degree, famous business man, Chief Executive Officer of Nuel Ojei Holdings Limited, and not forgetting his identity as a power broker of repute. Yes, until he death, he was one of the deciders of political inclinations and power shifts.

But on December 27, 2025, the curtain fell on his extraordinary humanitarian efforts, his life, his activities on the physical earth and his benevolence to his immediate, extended and adopted families across the world. He was 74 years when he breathe his last on that fateful day, five months short of his 75th birthday.

Fondly known as Nuel Ojei, the businessman passed away that Saturday night in his hometown, Issele-Uku, in Aniocha North Local Government Area of Delta State, as confirmed by his son, Chuks Ojei, in a statement issued on Sunday, December 28, 2025, on behalf of the family.

He described the loss as a profound shock and an irreplaceable personal tragedy.

“Words cannot fully capture the depth of our pain at this moment, as we struggle to come to terms with the sudden loss of a man who was not only our father but our strength, teacher, and moral compass.

“My father was more than a businessman; he was a builder of lives and legacies. A distinguished Nigerian industrialist, entrepreneur, and business magnate, he served as the Founder, Executive Chairman, and Chief Executive Officer of Nuel Ojei Holdings Ltd.

“Through discipline, resilience, and uncommon wisdom, he built enterprises that created opportunities, inspired excellence, and contributed meaningfully to national development.

“To many, he was a mentor and leader of rare integrity. To us, he was a loving father whose counsel guided our steps and whose values shaped our lives. He led with humility, strength, and compassion, touching countless lives across generations.

“His absence leaves a void that can never be filled, but his teachings and example will forever remain our guide. Though his passing signals the end of a remarkable chapter, his legacy lives on in the institutions he built, the people he mentored, and the values he upheld.

“He is survived by his children, family members, and a wide community of friends, associates, and admirers who will continue to honour his memory.

“On behalf of the Ojei family, I humbly ask for your prayers, love, and support during this time of deep grief. Funeral arrangements and further details will be communicated in due course. An icon has fallen. A father is gone. His legacy will live forever.”

The story of Nuel Ojei is that of accomplishment, fulfillment and a typical example of I came, I saw, I conquer. He was part of everything he met. He didn’t just mentor folks, he saw them through from.scratch to finish; in business, politics and other aspects of life. He was the dreamers light.

Perhaps Nuel Ojei would still have been alive today as contrary to popularly held view, he was not under the strain of any undisclosed illness, was hail and hearty prior to his traveling to Asaba, then to his hometown, from where he returned to his maker. This is if, according sources, he not insisted on traveling to his hometown to celebrate the Christmas with his wife and family, whom he missed so much, contrary to his German doctor’s instruction.

Sources told The Boss exclusively that Ojei, who left Nigeria for Spain on December 10, returned to Abuja on December 22, and insisted on traveling to Asaba to join his family even when the doctor told him it wasn’t proper considering that he was under serious stress and fatigue. But he insisted, saying he missed his wife, who she has not seen close to a month, and would wish to spend the Christmas with the family. It was during his holidays at his country home that he asked away.

Nuel was one business minded individual, who began his business craft very early in life, hitting limelight in his 20s, becoming a millionaire, and buying his first house at the age of 29. He was already a big boy when he founded Nuel Ojei Limited in 1989, nurtured it in the early stages of vehicle distributorship with Rutam Motors, sole agent for Mazda, and partnership with Mercedes Benz, till it became a conglomerate.

In 1999, as Nuel Holdings was expanded, as he was diverting into many other enterprises, he bought the magnificent edifice at Mobolaji Bank Anthony Way, Ikeja, towards the airport, which was a furniture company. Honestly, the billionaire has a penchant for airport axis as Nuel Ojei Holdings head office in Abuja, sits glistening in the uphill sun, facing the Nnamdi Azikiwe Airport. Report has it that he bought the Ikeja property at a whooping cost of N1.2 billion in 1999 from the Labanese. With about four very gigantic warehouses therein, his furniture business kickstarted, and continued to make waves. Nuel is blessed with the Midas touch, and so every of his businesses has received the growth syndrome.

A cross section of individuals, who spoke to The Boss, confirmed in no few words of how lavishly benevolent the entrepreneur par excellence was.

“His giving was not limited. He gave to all and sundry; whether you already have or not,” a beneficiary confided in The Boss.

Those who know Ojei in his lifetime believe he was richer than any rich man in Nigeria today. “What Nigerian billionaires have is not money compared to Ojei’s solvency. He was very rich, and spends it without a care for the good of humanity,” a source told The Boss.

Among the many properties he has scattered across the world include houses in various capitals in Nigeria vis a vis Lagos, Abuja, Port Harcourt and more. He also has houses in France, from where his two private jets operate, Germany and other parts of the world. In addition, he boasts of the most expensively and expansively constructed edifice in the world, situated in his Isele Uku, Asaba, Delta State locality.

The sprawling edifice, which took about six years to construct, is a the palace of some sort, fit only for royalty. It is situated on a 35-dunam (roughly 10-acre) plot near the village of Issele-Uku in the Delta state, and covers an area of 12,000 square meters. A brief description of the masion has it that it is divided between a basement, an entrance floor and a residential floor, and among a large number of buildings, including a servants’ house and an entry pavilion used by the security guards.

In addition to all other qualities the gigantic house can boast of are cinema hall, discotheque, hair salon, bowling alley and separate 350-square-meter suites for the couple (Ojei and wife), as well as a selection of guest suites. It also has its own water-purification system and electrical generator.

In his garages are states of the art vehicles including Rolls Royce, Hummer jeeps, Mercedes Benz of various luxurious makes, Range Rovers, G-wagons…just name it. Sources say the number of automobiles in his Lagos home garage alone exceed 50. That’s how super wealthy Ojei was.

Born Emmanuel Isichei Ugochukwu Ojei on May 23, 1951 to military officer, who was during his time in the army superior to a onetime Nigeria’s Head of State, Nuel had both primary and secondary education in the locality of his birth, Lagos before relocating to his hometown attend the Issele Uku Technical College, Issele Uku, between 1970 and 1972. He obtained a National Diploma in Business Administration and Management in the bargain.

It was after the ND education that he concentrated on personal building, business-wise, and returned to Lagos, and took up a job as a Sales Executive at Rutam Motors Ltd, owned by the Ibru Family, known for their super wealth.

In 1976, he left the job after attaining the position of Sales Manager. He thereafter joined Kapital Assurance Ltd in 1977, and rose to become a Director.

With hands in so many pies, Ojei learnt the craft of mastering all endeavours. He was into supplies of military wares during the 1980s, banking, and was reputed to once owned a bank, insurance, construction and telecommunications.

His interest in the oil and gas industry was limitless as he is said to own three oil blocks, and had stakes in solid minerals, telecommunications, safety and security, as well as shipping and ship building. He was a master of all.

The story of Ojei is a case study, a reference point and a research material. He was one Nigeria, who said very little, but recorded and achieved so much. He mentored numerous persons, who are spreading wealth as well across the length and breadth of capacity development and transfer.

The NOH identity is a focused, determined and committed brand that Ojei had used to affect humanity.

As wealthy as he was, he married only one wife, and is blessed with five great children, who are living the dream in its clear 8-letters of positive.

It must be noted as well that Ojei’s must treasured belonging other than his family, is the honorary doctorate honours he received from the Delta State University for his business acumen and impact on humanity. To him, that award is from home, and when your home identifies with you, you have nothing to worry about.

Emmanuel Isichei Ugochukwu Ojei may have bowed out physically from the earth, but the legacies, he systematically created will live for generations and generations to come. He was not consistently in public view, but worked assidously behind the curtains to put laughter on the lips of so many individuals across the world.

May his industrious soul find rest in the bosom of the Lord…Amen!

Related

Boss Picks

Hon Jumoke Okoya-Thomas Becomes Otun Iyalode of Lagos

Published

4 weeks agoon

January 25, 2026By

Eric

By Eric Elezuo

In recognition of her wholesome performances and contributions to governance in Lagos State, the Oba of Lagos, also known as Eleko of Eko, Oba Rilwan Akiolu, has conferred a deserved chieftaincy title on former lawmaker, APC leader and prominent female politician in Lagos State, Hon Olajumoke Okoya-Thomas.

The notable woman-leader is now the Otun Iyalode of Lagos; an important traditional stool in the cultural affairs of Lagos, and the ancient city couldn’t hold its joy as it rolled it the drums in celebration.

With an avalanche of dignitaries, nobles and political giants from across the socio-economic strata of Lagos, the Iga Idunganran residence of the paramount ruler of Lagos, became another excursion site, unleashing deep-rooted culture, excellent camaraderie and impressive display of ingredients that make Lagos, popularly known as Eko thick.

The gathering boasted of the likes of Otunba Gbenga Daniel, Sir Kesington Adebutu, Prince Samuel Adedoyin & wife, Pastor Ituah Ighodalo of Trinity House, Speaker of Lagos State House of Assembly, Rt. Hon Mudashiru Obasa, Governor of Lagos State, Mr. Babajide Sanwolu & wife, Chairperson, Diaspora Commission, Mrs. Abike Dabiri-Erewa, Chief Mrs Sena Anthony, Mr Ladi Adebutu, Mr Segun Adebutu, Firstlady of Ogun State, Mrs Bamidele Abiodun, HRM Oba Abdulwasiu Omogbolahan Lawal & Olori Mariam, HRM Oba Ibikunle Fafunwa Onikoyi, Alara of Ilara Oba Olufolarin Ogunsanwo, Olugbon of Orile Igbon, Oba Francis Alao & Olori, Chief Mrs Bisi Abiola, Olori Vicky Hastrup, Senator Sade Bent, Deputy Governor of Lagos State, Mr Babafemi Hamzat and Mr Tope Abere.

Others include Hon Kafilat Ogbara, Alhaji Tajudeen Okoya and Chief Durisimi Etti, who were also conferred with various chieftaincy honours.

As Hon Okoya-Thomas stepped out in grace, clad in all white, and adorned with precious ornaments; symbol of her royalty, the Oba was on hand to dish out the ‘sayings’, with the assistance of his white cap chiefs, that bestowed on her the powers and privileges of the Otun Iyalode.

Thereafter, a sumptuous reception was held at the Condo, Airforce Base, Victoria Island, where guests were treated to the best of entertainment ranging from good food, good music, good beverages and good networking under the very hilarious guidance of popular MC, Tee A. It was a night of solidarity for a woman, who has and is still giving her best to humanity and to society.

The atmosphere did not experience a dull moment as popular musician, Ayo Balogun serenaded the audience with soulful sounds, creating an environment, where the celebrant and her guests shuffled unhindered to the smooth ride of powerful renditions.

Earlier, and prior to the event, President Bola Tinubu had sent a heartwarming congratulatory message to the former lawmaker, who many believe is a highflyer and prominent Lagos politicians, wishing her well with regards to her double celebrations including her birthday on January 20, 2026, when she turned 69, and her receiving of the prestigious Otun Iyalode title, four days after.

In the statement signed by his Special Adviser, Information and Strategic, Bayo Onanuga, President Tinubu noted that “Jumoke Okoya-Thomas, the All Progressives Congress Women Leader in Lagos State, represented Lagos Island Federal Constituency in the House of Representatives for three consecutive terms, from 2003 to 2015.

“President Tinubu commends Okoya-Thomas for her contributions to the state and for her consistent efforts to increase women’s participation in politics and governance.

“The President also notes her chieftaincy title of Otun Iyalode of Lagos, describing it as appropriate and fitting, given her commitment to women’s empowerment and support for traditional institutions in Lagos.

“President Tinubu wishes Okoya-Thomas long life and good health, even as he prays for a successful chieftaincy ceremony.

THE JUMOKE THE WORLD KNOWS

As the new Otun Iyalode, a high ranking female chieftaincy title in Yoruba, Okoya-Thomas is saddled with the responsibility of performing leadership roles as well as being the spokesperson for all women in the community. S

She is also expected to play crucial roles in mediation of disputes, especially those involving women. She will participate in legislative functions and decision-making processes concerning the town’s welfare. These are responsibilities the all-experience former lawmaker is endowed with.

We therefore wish Madam Olajumoke Okoya-Thomas a happy 69th birthday, and gracious tenure as she navigates through the tasks of Otun Iyalode(ship).

Congratulations ma!

Related

Adding Value: Confidence and Succces by Henry Ukazu

Vexatious and Meddlesome: ADC Condemns Wike’s Tour of FCT Polling Units

Vote Buying, Low Turnout Mar FCT Polls – Yiaga Africa

The Power of Strategy in the 21st Century: Unlocking Extraordinary Possibilities (Pt. 2)

The Oracle: Entertainment, the Next Hope for Nigeria After Oil (Pt. 1)

Friday Sermon: Reflections on Ramadan 1: Prophet’s (SAW) Ramadan Sermon

I’m Proud of You, Osinbajo Tells Abia Gov Alex Otti

WAEC Releases 2025 CB-WASSCE for Private Candidates, Withholds 1899 Results

Alleged N432bn Fraud: El-Rufai Spends Monday Night in EFCC Custody

Ogbunechendo, Ooni Differ on Southern Traditional Rulers’ Council

Loyalty to APC Reason I’ll Oppose Gov Alex Otti in 2027 – Orji Kalu

FG Files Charges Against El-Rufai over NSA Phone-tapping Claims

Senate Passes Electoral Act Amendment Bill 2026

INEC Promises e-transmission of FCT Council Poll Results, Warns Against Vote-buying

Trending

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoWAEC Releases 2025 CB-WASSCE for Private Candidates, Withholds 1899 Results

-

Headline5 days ago

Headline5 days agoAlleged N432bn Fraud: El-Rufai Spends Monday Night in EFCC Custody

-

Featured5 days ago

Featured5 days agoOgbunechendo, Ooni Differ on Southern Traditional Rulers’ Council

-

Featured4 days ago

Featured4 days agoLoyalty to APC Reason I’ll Oppose Gov Alex Otti in 2027 – Orji Kalu

-

Headline6 days ago

Headline6 days agoFG Files Charges Against El-Rufai over NSA Phone-tapping Claims

-

National5 days ago

National5 days agoSenate Passes Electoral Act Amendment Bill 2026

-

Featured3 days ago

Featured3 days agoINEC Promises e-transmission of FCT Council Poll Results, Warns Against Vote-buying

-

Featured3 days ago

Featured3 days agoI’m Proud of You, Osinbajo Tells Abia Gov Alex Otti