Opinion

The Oracle: Why Nigeria Needs Restructuring (Pt. 4)

Published

3 years agoon

By

Eric

By Mike Ozekhome

INTRODUCTION

The word restructuring has become the latest word in the political landscape with political and non political actors pushing forward their ideas of the word that was not too long ago, abhorrence to many stage actors. Today, we shall x-ray further why Nigeria needs restructuring.

NIGERIA’S EARLIER PANACEA THROUGH TRUE FISCAL FEDERALISM

Before the 15th January, 1966 Military Coup led by Major Kaduna Nzeogwu Chukwuma from Okpanam, Nigeria operated true fiscal federalism amongst the then three regions-Western, Northern and Eastern Regions. They were later joined by the Midwest region which was excised out of Western region by popular Plebiscite and referendum on the 10th of August, 1963. The Architects of that federalist feat were Dr Dennis Osadebay (later Prime Minister); Oba Akenzua II; Dr Christopher Okojie; Justice Kessington Momoh, Chief James Otoboh, Chief Humphrey Omo-Osagie; Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh (Omimi Ejoh), Chief Jereton Mariere and Chief David Edebiri, the Esogban of Benin Kingdom.

Section 140 of the 1963 Republican Constitution which replicated section 134 of the 1960 Independence Constitution provided that 50% proceeds of royalty received by the Federation in respect of minerals extracted from a region, including any mining rents derived by the federation belonged to a Region. Effectively, this made the Regions which also had their separate regional Constitution (with a Federal one at the centre) to control their resources. Only 20% was paid to the Federation; and another 30% shared by all the Regions, including those that had already shared 50%.

In the Northern Region, Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Northern Premier who had sent his NPC Deputy (Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa) to the centre to be Prime Minister, preferring to govern his people, utilized the resources of Northern Nigeria. With the famous Kano groundnut pyramid, cotton, Hides and skin, the imperious by cerebral Sardauna, who had valiantly fought for, but failed to become the Sultan of Sokoto at 29, losing to Sultan Siddiq Abubakar III, who reigned for 50 years till 1988. The great grandson of Uthman Dan Fodio (of “Conscience is an open wound; only the truth can heal it” fame), built the Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) which stretched from Samaru, Zaria, to Funtua in the present day Katsina. He set up the Northern Nigeria Development Company (NNDC); built the Yankari Games Reserve; the Ahmadu Bello Stadium; and the Hamdala hotel, Kaduna.

In the Eastern Region, Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe (First Premier 1954-1959) and later Dr Michael Okpara, and his Governor, Dr Akanu Ibiom and others with Dr Mbonu Ojike embarked upon major organ on revolution; they built the Trans-Amadi Industrial Estates and Presidential hotels in Enugu and Portharcourt. They built the University of Enugu; the Obudu Cattle Ranch and Resort, the Eastern Nigeria Development Corporation (ENDC); Cement fatory at Nkalagu, breweries, textile Mills and Enugu Stadium. They could do this because they controlled their palm produce. This was time fiscal federalism at work.

In western Region, the late Sage, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, used proceeds from the coca product to build the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Corporation, the first television station in Africa, (1957); introduced free universal primary education and free health service; The liberty stadium and Cocoa House in Ibadan and the University of Ife (now OAU) were built by him. Because he controlled the resources of the West.

In the Mid west Region, Dr Dennis Osadebay spear headed the setting up of the Ughelli Glass Industry and the Okpellla Cement Factory, amongst others. What has changed? Why do we now operate a Unitary System of government, with centralized powers, a behemoth Central federal government and beleaguered, subservient states as federating units. Commissioners for finance congregate at Abuja at the end of every month to take state allocations under section 162 of the 1999 Constitution. Nigeria can never grow that way.

So much for the diagnosis. What about the prognosis? Is there a way back or out of this self-inflicted cocktail of challenges? If so, what does it take – and how do we realize or achieve it? In other words, what is the solution to the puzzle implied in the title of this piece? How do we pull Nigeria from the brink? There is no doubt that there are no easy answers to these posers and it is simplistic to assume that what has been tried successfully elsewhere will necessarily work here. In other words, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. It is equally true, however, that, while it is fool-hardy to seek to re-invent the wheel, valuable lessons can be learned from those who have trodden similar paths as ours and have emerged stronger, more prosperous and stable in every possible way. Indeed, in some cases – particularly, the so-called ‘Asian Tigers’, their transformation from Third World status to First World economies, has been as dramatic as it is unprecedented. How did they achieve it? Is there any magic wand? Is it appropriate to apply them to Nigeria or would that be comparing grapes to apples?

THE ASIAN TIGERS: HOW THEY DID IT

I believe the answers to all these posers are self-evident, given the common history of backwardness and virtually complete non-industrialization (with the exception of Japan) which the so-called Asian Tigers shared with Nigeria at independence. This is because all the Tigers – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Indonesia – were, like Nigeria, under prolonged periods of colonial and/or military rule. Even Japan, which was a relatively prosperous and industrialized society, prior to the Second World War, had to start virtually from scratch afterwards, following its defeat in that conflict. Accordingly, these comparisons are in no way odious. The question, then is: how did these countries do it? In terms of strategy, it appears that the following are key to the seeming miracle achieved by these erstwhile developing countries:

- Investment in skills;

- Advancements in Technology;

- Engagement of specialized agencies;

- Establishment of pilot projects; and

- Involvement of International Agencies such as the U.N.

LESSONS FOR NIGERIA FROM THE ASIAN TIGERS

Scholars have suggested that Nigeria can benefit from the experience of the Asian Tigers in the following ways:

- Formulating and implementing deliberate government policies;

- Strengthening the development of agriculture;

- Encouraging industrial development;

- Developing small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs).

The following have also been proffered as additional take-away from the ‘miracle’ of the Asian Tigers, which can be adopted or applied profitably in Nigeria, viz:

Focus on exports. Domestic production should be encouraged especially targeted at exports, through government policies such as high import tariffs to discourage the latter;

Human capital development. This focuses on developing specialized skills aimed at enhancing productivity through improved educational standards;

Creating a sound financial system. A well- developed capital market will facilitate mobilization of capital for industrial and economic development;

Maintenance of political, social as well as macroeconomic stability;

Leadership that priorities citizens’ welfare thereby motivating labour to increase productivity;

Encouraging a savings culture in order to increase capital formation (preferably through private institutions);

Developing export-oriented industries to produce selected goods with a relatively competitive advantage in world markets,

The Specific Case of Japan

The following have been identified as lessons for Nigeria from the so-called ‘Japanese Miracle’, viz:

Massive investments in research and development with a view to developing, inter alia, efficient production techniques;

Adaptation of foreign/imported technology;

Massive investments in infrastructure and heavy manufacturing industries;

Proper and prudent management of our natural resources (particularly oil and gas);

A disciplined, relatively cheap, highly educated and skilled work-force, with reasonable wage demands;

Targeting high literacy rate and high education standards;

Private Sector-driven investment. The profit incentive of the private sector results in large-scale investment culminating in economies of scale in production.

WHAT OF EUROPE AND THE U.S.?

In addition to the foregoing, it does appear that both Europe and the US offer valuable lessons in economic integration or co-operation with regional countries which will eliminate waste and create economies of scale and increase investment levels.

THE BIG PICTURE

On a broader, political and macro-economic level, Onigbinde identified the following as key issues in the quest to solve the riddle of “How to Fix Nigeria,” viz: – Enhancing Security; Promoting National Unity; Improving Public Health; Economic Competitiveness and Diversity (away from oil and natural gas); Tackling the Revenue or Income Challenge; Putting People to Work; and Governance Accountability. He, then, concludes, insightfully, that “Nigeria will only move forward as a nation forged in unity, by optimizing every single public resource and making the health, safety and prosperity of its people an urgent concern. There are no short-cuts; fixing Nigeria requires a consistent, long-term approach, not those constantly watching four-year elections, like a ‘dieter watching the scale every hour”.

To the foregoing, we agree that tackling corruption, promoting the rule of law, and strengthening civil society organizations, are also relevant touchstones. Beyond even that, however, we must include leadership by example, as well as re-orientation of the citizenry on the benefits of a new national ethos of true patriotism, which de-emphasizes the prevailing culture of primitive acquisition of wealth by all means, fair or foul – and its obscene display.

The benefits of a committed and conscientious, leadership-driven attempt at re-directing the Nigerian ship away from its calamitous down-ward slide, are too obvious to need re-telling. Suffice it to say that it might literally be the difference between our survival as a nation and our much-predicted collapse or fragmentation into any number of sub-national, ethnic-based units. In other words, the challenge is simply existential. Such an outcome should be avoided at all costs – unless its benefits outweigh its costs. Such perceived benefits are, frankly, hard to envisage and, the more desirable option is to cultivate an elite consensus towards an orderly resolution by means of a suitable medium – such as a referendum.

Though it seems that many are averse to the potential outcome of this option (because, it is apparently a Pandora’s Box of sorts), the alternative might be far worse, with some predicting a Somalia-style No Man’s Land where there is no viable Central Government worthy of that name and where literally anything goes. This scenario might be unduly pessimistic but, the possibility that it will become our reality is a scenario which no reasonable person can dismiss with a wave of the hand. All hands must, therefore, be on deck to save this ship. This nation must not fail and, by the grace of God, it will not fail.

Given the above depressing scenario and narrative, the question to be asked is: how did we get here and how can be ‘get out of jail,’ as it were? How do we resolve our diverse, hydra-headed challenges?

THE IMPERATIVE OF STRUCTURAL REFORM: HOW DO WE REFORM STRUCTURALLY?

A BRAND NEW OR AN AMENDED CONSTITUTION?

Many solutions have been suggested, with constitutional amendment or reenactment top of the list. The reason is obvious: it is a country’s birth certificate; the foundation, basis or as we call it in law, the grundnorm. In this regard The 1999 Constitution is the product of the military led by General Abdusalami Alhaji Abubakar. The explanatory note to the said Constitution is worth considering as it explains the purport of the Constitution. The explanatory note to the 1999 Constitution (the subject matter of this article), states thus: “The Decree promulgates the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 199 into law and provides for the said Constitution to come into force on 29th May, 1999.” The explanatory note above contains extra information to the effect that the explanatory: “…note does not form part of the above Decree but is intended to explain its purport.” The term “promulgate” means to spread an idea, a belief, etc. among the people. Whose beliefs and ideas are the military spreading and at what point did this idea or belief come into force? It is pertinent to note that the 1999 Constitution divested the military over the governance of Nigeria and re-enforces the original ideas and beliefs of the people at the time they got independence. (To be continued).

THOUGHT FOR THE WEEK

“People always want welfare, development, and good governance. As long as you are delivering, people are with you”. (N. Chandrababu Naidu).

Related

You may like

Opinion

A Holistic Framework for Addressing Leadership Deficiencies in Nigeria, Others

Published

1 day agoon

February 6, 2026By

Eric

By Tolulope A. Adegoke PhD

“Effective leadership is not a singular attribute but a systemic outcome. It is forged by institutions stronger than individuals, upheld by accountability with enforceable consequences, and sustained by a society that demands integrity as the non-negotiable price of power. The path to renewal—from national to global—requires us to architect systems that make ethical and competent leadership not an exception, but an inevitable product of the structure itself” – Tolulope A. Adegoke, PhD

Introduction: Understanding the Leadership Deficit

Leadership deficiencies in the modern era represent a critical impediment to sustainable development, social cohesion, and global stability. These shortcomings—characterized by eroded public trust, systemic corruption, short-term policymaking, and a lack of inclusive vision—are not isolated failures but symptoms of deeper structural and ethical flaws within governance systems. Crafting effective solutions requires a clear-eyed, unbiased analysis that moves beyond regional stereotypes to address universal challenges while respecting specific contextual realities. This document presents a comprehensive, actionable framework designed to rebuild effective leadership at the national, continental, and global levels, adhering strictly to principles of meritocracy, accountability, and transparency.

I. Foundational Pillars for Systemic Reform

Any lasting solution must be built upon a bedrock of core principles. These pillars are universal prerequisites for ethical and effective governance.

1. Institutional Integrity Over Personality: Systems must be stronger than individuals. Governance should rely on robust, transparent, and rules-based institutions that function predictably regardless of incumbents, thereby minimizing personal discretion and its attendant risks of abuse.

2. Uncompromising Accountability with Enforceable Sanctions: Accountability cannot be theoretical. It requires independent oversight bodies with real investigative and prosecutorial powers, a judiciary insulated from political interference, and clear consequences for misconduct, including loss of position and legal prosecution.

3. Meritocracy as the Primary Selection Criterion: Leadership selection must transition from patronage, nepotism, and identity politics to demonstrable competence, proven performance, and relevant expertise. This necessitates transparent recruitment and promotion processes based on objective criteria.

4. Participatory and Deliberative Governance: Effective leaders leverage the collective intelligence of their populace. This demands institutionalized channels for continuous citizen engagement—beyond periodic elections—such as citizen assemblies, participatory budgeting, and formal consultation processes with civil society.

II. Context-Specific Strategies and Interventions

A. For Nigeria: Catalyzing National Rebirth Through Institutional Reconstruction

Nigeria’s path requires a dual focus: dismantling obstructive legacies while constructing resilient, citizen-centric institutions.

· Constitutional and Electoral Overhaul: Reform must address foundational structures. This includes a credible review of the federal system to optimize the balance of power, the introduction of enforceable campaign finance laws to limit monetized politics, and the implementation of fully electronic, transparent electoral processes with real-time result transmission audited by civil society. Strengthening the independence of key bodies like INEC, the judiciary, and anti-corruption agencies through sustainable funding and insulated appointments is non-negotiable.

· Genuine Fiscal Federalism and Subnational Empowerment: The current over-centralization stifles innovation. Empowering states and local governments with greater fiscal autonomy and responsibility for service delivery would foster healthy competition, allow policy experimentation tailored to local contexts, and reduce the intense, often violent, competition for federal resources.

· Holistic Security Sector Reform: Addressing insecurity requires more than hardware. A comprehensive strategy must include community-policing models, merit-based reform of promotion structures, significant investment in intelligence capabilities, and, crucially, parallel programs to address the root causes: youth unemployment, economic inequality, and environmental degradation.

· Investing in the Civic Infrastructure: A functioning democracy requires an informed and engaged citizenry. This mandates a national, non-partisan civic education curriculum and robust support for a free, responsible, and financially sustainable press. Protecting journalists and whistleblowers is essential for maintaining transparency.

B. For Africa: Leveraging Continental Solidarity for Governance Enhancement

Africa’s prospects are tied to its ability to act collectively, using regional and continental frameworks to elevate governance standards.

· Operationalizing the African Governance Architecture: The African Union’s mechanisms, particularly the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), must transition from voluntary review to a system with meaningful incentives and consequences. Compliance with APRM recommendations could be linked to preferential access to continental infrastructure funding or trade benefits under the AfCFTA.

· The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) as a Governance Catalyst: Beyond economics, the AfCFTA can drive better governance. By creating powerful cross-border commercial interests, it builds domestic constituencies that demand policy predictability, dispute resolution mechanisms, and regulatory transparency—all hallmarks of sound leadership.

· Pan-African Human Capital Development: Strategic investment in continental human capital is paramount. This includes expanding regional centers of excellence in STEM and public administration, fostering academic and professional mobility, and deliberately cultivating a new generation of technocrats and leaders through programs like the African Leadership University.

· Consistent Application of Democratic Norms: Regional Economic Communities (RECs) must enforce their own democratic charters uniformly. This requires establishing clear, automatic protocols for responding to unconstitutional changes of government, including graduated sanctions, rather than ad-hoc diplomatic responses influenced by political alliances.

C. For the Global System: Rebuilding Equitable and Effective Multilateralism

Global leadership crises often stem from outdated international structures that lack legitimacy and enforceability.

· Reforming Archaic Multilateral Institutions: The reform of the United Nations Security Council to reflect 21st-century geopolitical realities is essential for its legitimacy. Similarly, the governance structures of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank must be updated to give emerging economies a greater voice in decision-making.

· Combating Transnational Corruption and Illicit Finance: Leadership deficiencies are often funded from abroad. A binding international legal framework is needed to enhance financial transparency, harmonize anti-money laundering laws, and expedite the repatriation of stolen assets. This requires wealthy nations to rigorously police their own financial centers and professional enablers.

· Fostering Climate Justice and Leadership: Effective global climate action demands leadership rooted in equity. Developed nations must fulfill and be held accountable for commitments on climate finance, technology transfer, and adaptation support. Leadership here means honoring historical responsibilities.

· Establishing Norms for the Digital Age: The technological frontier requires new governance. A global digital compact is needed to establish norms against cyber-attacks on civilian infrastructure, the use of surveillance for political repression, and the cross-border spread of algorithmic disinformation that undermines democratic processes.

III. Universal Enablers for Transformative Leadership

Certain interventions are universally applicable and critical for cultivating a new leadership ethos across all contexts.

· Strategic Leadership Development Pipelines: Nations and institutions should invest in non-partisan, advanced leadership academies. These would equip promising individuals from diverse sectors with skills in ethical decision-making, complex systems management, strategic foresight, and collaborative governance, creating a reservoir of prepared talent.

· Redefining Success Metrics: Moving beyond Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as the primary scorecard, governments should adopt and be assessed on holistic indices that measure human development, environmental sustainability, inequality gaps, and citizen satisfaction. International incentives, like preferential financing, could be aligned with performance on these multidimensional metrics.

· Creating a Protective Ecosystem for Accountability: Robust, legally enforced protections for whistleblowers, investigative journalists, and anti-corruption officials are fundamental. This may include secure reporting channels, legal aid, and, where necessary, international relocation support for those under threat.

· Harnessing Technology for Inclusive Governance: Digital tools should be leveraged to deepen democracy. This includes secure platforms for citizen feedback on legislation, open-data portals for public spending, and digital civic assemblies that allow for informed deliberation on key national issues, complementing representative institutions.

Conclusion: The Collective Imperative for Renewal

Addressing leadership deficiencies is not a passive exercise but an active, continuous project of societal commitment. It requires the deliberate construction of systems that incentivize integrity and penalize malfeasance. For Nigeria, it is the arduous task of rebuilding a social contract through impartial institutions. For Africa, it is the strategic use of collective action to elevate governance standards continent-wide. For the world, it is the courageous redesign of international systems to foster genuine cooperation and justice. Ultimately, the quality of leadership is a direct reflection of the standards a society upholds and enforces. By implementing this multilayered framework—demanding accountability, rewarding merit, and empowering citizens—a new paradigm of leadership can emerge, transforming it from a recurrent source of crisis into the most reliable engine for human progress and shared prosperity.

Dr. Tolulope A. Adegoke, AMBP-UN is a globally recognized scholar-practitioner and thought leader at the nexus of security, governance, and strategic leadership. His mission is dedicated to advancing ethical governance, strategic human capital development, and resilient nation-building, and global peace. He can be reached via: tolulopeadegoke01@gmail.com, globalstageimpacts@gmail.com

Related

Opinion

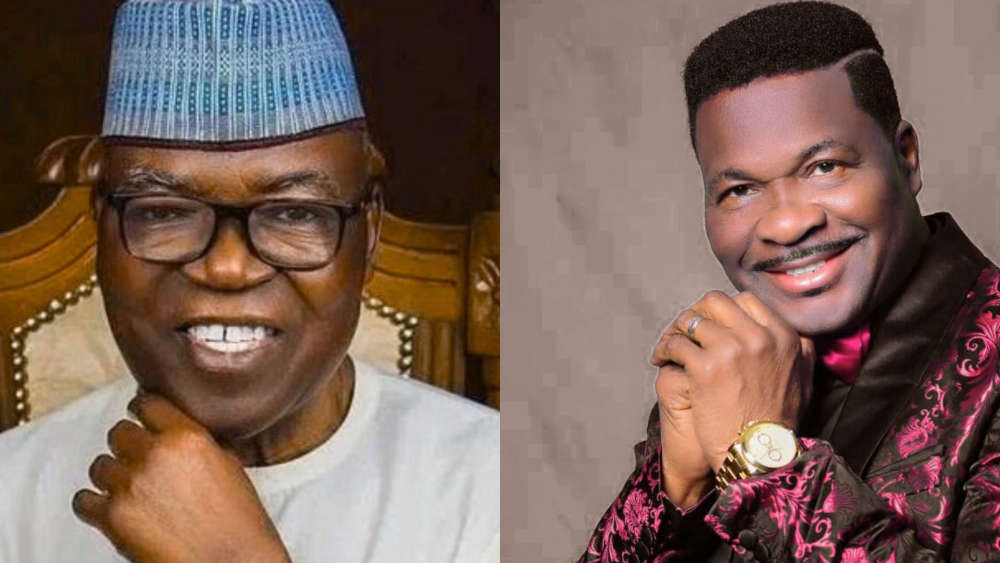

Tali Shani vs Mike Ozekhome: How a Legal Mole-Hill Was Turned into a Mountain

Published

1 day agoon

February 6, 2026By

Eric

By Abubakar D. Sani, Esq

INTRODUCTION

News of the decision of a British Tribunal in respect of a property situate in London, the UK’s capital, whose ownership was disputed has gained much publicity since it was delivered in the second week of September 2025. For legal reasons, the charges brought against prominent lawyer, Chief Mike Ozekhome, SAN, based on same is the most that can be said of it as no arraignment was made before Hon. Justice Kekemeke of the High court of the FCT, Abuja, sitting in Maitama.

Accordingly, this intervention will be limited to interrogating the common, but false belief (even in legal circles), that the Tribunal somehow indicted him with conclusive ‘guilt’. I intend to argue that this belief is not correct; and that, on the contrary, nothing could be further from the truth. For the sake of context, therefore, it is necessary to refer to relevant portions of the decision of Judge Paton (the name of the Tribunal’s presiding officer), which completely exonerated Chief Ozekhome, but which his detractors have always conveniently suppressed.

WHAT DID THE TRIBUNAL SAY?

Not a few naysayers, smart-alecs, emergency analysts and self-appointed pundits have been quick to latch on to some passages in the judgement of the Tribunal which disagreed with Ozekhome’s testimony to justify their crucifixion of Chief Ozekhome – even without hearing his side of the story or his version of events. This is a pity, of course, especially for the supposedly learned senior lawyers among them who, by ignoring the age-old principle of fair hearing famously captured as audi alterem partem (hear the other side) have unwittingly betrayed patent bias, malice, malevolence and utter lack of bona fides as the major, if not exclusive, motivator of their view-points and opinions. I have particularly watched about five of such senior lawyers shop from one platform to another, with malicious analysis to achieve nothing, but reputational damage. They know themselves.

Before proceeding to those portions, it is important to acknowledge that the Tribunal conducted a review of the evidence placed before it. The proceedings afforded all parties the opportunity to present their respective cases. The learned Judge carefully evaluated the testimonies, documentary exhibits and surrounding circumstances and rendered a reasoned decision based on the materials before the Tribunal.

It is also not in doubt that the Tribunal made certain critical observations in the course of assessing the credibility of the witnesses and the plausibility of their explanations. Such evaluative comments are a normal and inevitable feature of judicial fact-finding, particularly in property tribunals in contested proceedings involving complex transactions and disputed narratives. They do not amount to indictment.

It is precisely the improper isolation and mischaracterization of some of these observations that have given rise to the present misconception that the Tribunal somehow pronounced a verdict of guilt on Chief Ozekhome. It is therefore necessary to place the relevant excerpts in their proper legal and factual context, so as to demonstrate how the self-same tribunal exonerated Ozekhome.

“Paragraph 98: Once one steps back from that material, and considers the Respondent’s own direct personal knowledge of relevant matters relating to this property, this only commences in 2019. That is, he confirmed, when he was first introduced to Mr. Tali Shani – he thought in about January of that year. He did not therefore know him in 1993, or at any time before January 2019. He could not therefore have any direct knowledge of the circumstances of the purchase of this property, or its management prior to 2019. He had, however, known the late General Useni for over 20 years prior to his death, as both his lawyer and friend.

“Paragraph 103: Such of the Respondent’s written evidence had been about the very recent management of the property, and in particular his dispute over its management (and collection of rents) with one Nicholas Ekhorutowen, who provided no evidence in this case. The Respondent confirmed in oral evidence that it was upon the execution of the powers of attorney that he came into possession of the various pre registration title and conveyancing documents which formed part of his disclosure. These had been handed over to him by the next witness who gave evidence, Mr. Akeem Johnson.

“Paragraph 168: Unlike the fictitious “Ms. Tali Shani”, a man going by the name of Mr. Tali Shani exists and gave evidence before me in that name. A certified copy of an official Nigerian passport was produced both to the Land Registry and this Tribunal, stating that Mr. Tali Shani was born on 2nd April 1973. I do not have the evidence, or any sufficient basis, to find that this document – unlike the various poor and pitiful forgeries on the side of the “Applicant” – is forged, and I do not do so.

“Paragraph 200: First, I find that General Useni, since he was in truth the sole legal and beneficial owner of this property (albeit registered in a false name), must in some way have been connected to this transfer, and to have directed it. He was clearly close to, and on good terms with, the Respondent. There is no question of this being some sort of attempt by the Respondent to steal the general’s property without his knowledge.

“Paragraph 201: As to precisely why General Useni chose to direct this transfer to the Respondent, I do not need to (and indeed cannot) make detailed findings. I consider that it is highly possible that it was in satisfaction of some debt or favour owed. The Respondent initially angrily denied the allegation (made in the various statements filed on behalf of the “Applicant”) that this was a form of repayment of a loan of 54 million Naira made during the general’s unsuccessful election campaign. In his oral evidence, both he and his son then appeared to accept that the general had owed the Respondent some money, but that it had been fully paid off. The general himself, when asked about this, said that he “did not know how much money he owed” the Respondent.

“Paragraph 202: I do not, however, need to find precisely whether (and if so, how much) money was owed. The transfer may have been made out of friendship and generosity, or in recognition of some other service or favour. The one finding I do make, however, is that it was the decision of General Useni to transfer the property to the Respondent.”

It must be emphasised that even where a court finds that a witness has given inconsistent, fluctuating, or implausible testimony, as some have latched on, such a finding does not, without more, translate into civil or criminal liability. At best, it affects the weight and credibility to be attached to such evidence. It does not constitute proof of fraud, conspiracy, or criminal intent. See MANU v. STATE (2025) LPELR-81120(CA) and IKENNE vs. THE STATE (2018) LPELR-44695 (SC)

Notwithstanding the Tribunal’s engagement with the evidence, certain passages had been selectively extracted and sensationalised by critics. On the ipssisima verba (precise wordings) of the Tribunal, only the above paragraphs which are always suppressed clearly stand out in support of Chief Ozekhome’s case, as the others were more like opinions.

Some paragraphs in the judgement in particular, appear to have been carefully selected as “weapons” in Chief Ozekhome’s enemies’ armoury, as they are most bandied about in the public space. The assumption appears to be that such findings are conclusive of his guilt in a civil property dispute. This is unfortunate, as the presumption of innocence is the bedrock of our adversarial criminal jurisprudence. It is a fundamental right guaranteed under section 36 of the Constitution and Article 7 of the African Charter which, regrettably, appear to have been more observed in the breach in his case.

More fundamentally, the selective reliance on few passages that disagreed with his evidence or testimony and that of Mr. Tali Shani, ignore the above wider and more decisive findings of the Tribunal itself. A holistic reading of the judgment reveals that the Tribunal was far more concerned with exposing an elaborate scheme of impersonation, forgery, and deception orchestrated in the name of a fictitious Applicant, Ms Tali Shani, and not Mr. Tali Shani (Ozekhome’s witness), who is a living human being. These findings, which have been largely ignored in public discourse, demonstrate that the gravamen of the Tribunal’s decision lay not in any indictment of Chief Ozekhome, but in the collapse of a fraudulent claim against him, which was founded on false identity and fabricated documents.

The Tribunal carefully distinguished a fake “Ms” Tali Shani (the Applicant), who said she was General Useni’s mistress and owner of the property, and the real owner, Mr Tali Shani, who was Chief Ozekhome’s witness before the Tribunal. It was the Tribunal’s finding that she was nothing but a phantom creation and therefore rejected her false claim to the property (par. 123). It also rejected the evidence of her so called cousin (Anakwe Obasi) and purported son (Ayodele Obasi) (par. 124).

The Tribunal further found that it was the Applicant and her cohorts that engaged in diverse fraud with documents such as a fraudulent witness statement purportedly from General Useni; all alleged identity documents; fabricated medical correspondence; the statement of case and witness statements; a fake death certificate; and a purported burial notice. (Paragraph 125). Why are these people not concerned with Barrister Mohammed Edewor, Nicholas Ekhoromtomwen, Ayodele Damola, and Anakwe Obasi? Why mob-lynching Chief Ozekhome?

The Tribunal found that the proceedings amounted to an abuse of process and a deliberate attempt to pervert the course of justice. It therefore struck out the Applicant’s claim (Paragraphs 130–165). The Tribunal significantly found that Mr Tali Shani exists as a human being and had testified before it in June, 2024. It accepted a certified Nigerian passport he produced, and accepted its authenticity and validity (Paragraph 168). Can any objective person hold that Ozekhome forged any passport as widely reported by his haters when the maker exists?

Having examined the factual findings of the Tribunal and their proper context, the next critical issue is the legal status and probative value of such findings. The central question, therefore, is whether the observations and conclusions of a foreign tribunal, made in the course of civil proceedings, are sufficient in law to establish civil or criminal liability against a person in subsequent proceedings.

STATUS OF JUDGEMENTS UNDER THE LAW

The relevant statutory provisions in Nigeria are sections 59, 60, 61, 173 and 174 of the Evidence Act 2011, provide as follows, respectively:

Section 59: “The existence of any judgment, order or decree which by law prevents any court from taking cognisance of a suit or holding a trial, is a relevant fact, evidence of which is admissible when the question is whether such court ought to take cognisance of such suit or to hold such trial”;

Section 60(I): “A final judgment, order or decree of a competent court, in the exercise of probate. Matrimonial, admiralty or insolvency jurisdiction, which confers upon or takes away from any person any legal character. or which declares any person to be entitled to any such character or to be entitled to any specific thing, not as against any specified person but absolutely, is admissible when the existence of any such legal character, or the title of any such legal persons to an) such thing, is relevant (2) Such judgment, order or decree is conclusive proof (a)that any legal character which it confers accrued at the time when such judgment, order or decree came into operation; (b) that any legal character. to which it declares any such person to be entitled. accrued to that person at the time when such judgment order or decree declares it to have accrued to that person; (c) that any legal character which it takes away from any such person ceased at the time from which such judgment, order or decree declared that it had ceased or should cease; and (d) that anything to which it declares any person to be so entitled was the property of that person at the time from which such judgment. order or decree declares that it had been or should be his property”;

Section 61: “Judgments, orders or decrees other than those mentioned in section 60 are admissible if they relate to matters of a public nature relevant to the inquiry; but such judgments, orders or decrees are not conclusive proof of that which they state”

Section 173: “Every judgment is conclusive proof, as against parties and privies. of facts directly in issue in the case, actually decided by the court. and appearing from the judgment itself to be the ground on which it was based; unless evidence was admitted in the action in which the judgment was delivered which is excluded in the action in which that judgment is intended to be proved”.;

Section 174(1): “If a judgment is not pleaded by way of estoppel it is as between parties and privies deemed to be a relevant fact, whenever any matter, which was or might have been decided in the action in which it was given, is in issue, or is deemed to be relevant to the issue in any subsequent proceeding”;

(2):”Such judgment is conclusive proof of the facts which it decides, or might have decided, if the party who gives evidence of it had no opportunity of pleading it as an estoppel”.

It can be seen that the decision of the Tribunal falls under the purview of section 61 of the Evidence Act, as the provisions of sections 59 and 60 and of sections 173 and 174 thereof, are clearly inapplicable to it. In other words, even though some Judge Paton’s findings in respect of Chief Ozekhome’s testimony at the Tribunal relate to matters of public nature (i.e., the provenance and status of No. 79 Randall Avenue, Neasden, London, U.K and the validity of his application for its transfer to him) none of those comments or even findings is in any way conclusive of whatever they may assert or state (to use the language of section 60 of the Evidence Act).

In this regard, see the case of DIKE V NZEKA (1986) 4 NWLR pt.34 pg. 144 @ 159 where the Supreme Court construed similar provisions in section 51 of the old Evidence Act, 1948. I agree with Tar Hon, SAN (S. T. Hon’s Law of Evidence in Nigeria, 3rd edition, page 1041) that the phrase ‘public nature’ in the provision is satisfied where the judgement is clearly one in rem as opposed to in personam. It is pertinent to say a few words about both concepts, as they differ widely in terms of scope. The former determines the legal status of property, a person, a particular subject matter, or object, against the whole world, and is binding on all persons, whether they were parties to the suit or not. See OGBORU V IBORI (2005) 13 NWLR pt. 942 pg. 319 @407-408 per I. T. Muhammed, JCA (as he then was).

This was amplified by the apex court in OGBORU V UDUAGHAN (2012) LLJR -SC, where it held, per Adekeye, JSC that: “A judgment in rem maybe defined as the judgment of a court of competent jurisdiction determining the status of a person or thing as distinct from the particular interest of a party to the litigation. Apart from the application of the term to persons, it must affect the “res” in the way of condemnation forfeiture, declaration, status or title”.

By contrast, “Judgments ‘in personam’ or ‘inter partes’, as the name suggests, are those which determine the rights of parties as between one another to or in the subject matter in dispute, whether it be corporeal property of any kind whatever or a liquidated or unliquidated demand but which do not affect the status of either things or persons or make any disposition of property or declare or determine any interest in it except as between the parties (to the litigation). See HOYSTEAD V TAXATION COMMISSIONERS (1926) A. C. 155. These include all judgments which are not judgments in rem. None of such judgments at all affects any interest which third parties may have in the subject matter. As judgment inter partes, though binding between the parties and their privies, they do not affect the rights of third parties. See CASTRIQUE V IMRIE 141 E. R. 1062; (1870) L. R. 4H. L. 414”.

Suffice it to say that the decision of the London Property Tribunal was, in substance, one affecting proprietary rights in rem, in the sense that it determined the status and registrability of the property in dispute. However, it did not determine any civil or criminal liability, nor did it pronounce on the personal culpability of any party. The implication of this is that, even though the decision was in respect of a matter of a public nature, it was, nonetheless, not conclusive as far as proof of the status of the property, or – more importantly – Chief Ozekhome’s role in relation to it. Indeed, the property involved was not held to have been traced to the owner (General Useni) as having ever tried or convicted for owning same. I submit that the foregoing is the best case scenario in terms of the value of Judge Paton’s said decision, because under section 62 of the Evidence Act, (depending, of course, on its construction), it will fare even worse, as it provides that judgments “other than those mentioned in sections 59. 60 and 61 are inadmissible unless the judgment, etc is a fact in issue or is admissible under some other provision of this or any other Act”.

CONCLUSION

Some people’s usual proclivity to rush to judgment and condemn unheard any person (especially a high profile figure like Chief Ozekhome), has exposed him to the worst kind of unfair pedestrian analysis, malice, mud-slinging and outright name-calling especially by those who, by virtue of their training, ought to know better, and, therefore, be more circumspect, restrained and guarded in their utterances. This is all the more so because, no court of competent jurisdiction has tried or pronounced him guilty. It is quite unfortunate how some select lawyers are baying for his blood.

The decision of the London Tribunal remains what it is: a civil determination on attempted transfer of a property based on the evidence before it. It is not, and cannot be, a substitute for civil or criminal adjudication by a competent court. The presumption of innocence under Nigerian laws remains inviolable. Any attempt by commentators to usurp that judicial function through premature verdicts is not only improper, but inimical to the fair administration of justice.

Related

Opinion

The Atiku Effect: Why Tinubu’s One-Party Dream Will Never Translate to Votes in 2027

Published

2 days agoon

February 5, 2026By

Eric

By Dr. Sani Sa’idu Baba

It is deeply disappointing if not troubling to watch a former governor like Donald Duke accuse Atiku Abubakar of contesting for the presidency “since 1992” without identifying a single provision of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria that such ambition violates. Donald Duke was once widely regarded as one of the most intelligent and forward-thinking leaders of his generation, which makes it even more puzzling to understand what must have come over him to suddenly align with those throwing tantrums at others who are by far more competent, experienced, and eligible than themselves. While I acknowledge that Duke has recently moved to the ADC, the party that Atiku belongs to, Nigerians should not be distracted by his kind of rhetoric.

As former presidential candidate and ADC chieftain Chief Dele Momodu has repeatedly stated, “everyone is afraid of Atiku Abubakar,” particularly as the 2027 presidential election approaches. That fear, according to Momodu, explains the ongoing campaign of calumny against him. Donald Duke’s remarks therefore cannot be separated from this wider effort to diminish a man widely seen as the most formidable opposition figure in Nigeria today.

However, the issue of Donald Duke is not the central purpose of my message today. It is only incidental. The real purpose is to share what should be considered good news for Nigerians, the growing perception among ordinary citizens and the conversations happening daily at junctions, gatherings, markets, campuses, mosques, churches, and in the nooks and crannies of the country. The truth is that Nigerians are largely unbothered by the APC’s one-party state ambition. They are not impressed by forced defections or elite political gymnastics. What occupies their minds instead is the unrelenting presence of opposition, sustained hope, and the quiet but powerful confidence inspired by what has now become known as the “Atiku Effect”.

In my own opinion, which aligns with the thinking of many discerning Nigerians, no one in either the opposition or the ruling camps today appears healthier physically, mentally, socially and politically than Atiku Abubakar. Health is not determined by propaganda or ageism, but by function, resilience, and capacity. As we were taught in medical school, “healthspan, not lifespan, defines vitality,” and “physiological resilience is age-independent.” These principles make it clear that fitness, clarity of thought, stamina, cognitive and physiological reserve matter far more than the number of years lived. By every observable measure, Atiku remains fitter and more grounded than many who are younger but visibly exhausted by power.

It is no longer news that Nigeria is being pushed toward a one-party state through the coercion of opposition governors into the ruling APC. What is increasingly clear, however, is that this strategy reflects anxiety rather than strength. Nigerians understand that governors do not vote on behalf of the people, and defections do not automatically translate into electoral victory. This same script was played before, and history has shown that elite alignment cannot override popular sentiment. Just as it happened in 2015, decamping governors cannot save a sitting president when the people have already reached a conclusion.

This is where the Atiku Effect becomes decisive. Atiku Abubakar represents continuity of opposition, courage in the face of intimidation, and the refusal to surrender democratic space. His consistency reassures Nigerians that democracy is still alive and that power can still be questioned. This is precisely why Dele Momodu’s assertion that “everyone is afraid of Atiku Abubakar” resonates so strongly across the country. It is not fear of noise or recklessness, but fear of discipline, experience, and endurance.

Across Nigeria today, the ruling party is increasingly treated as the most unserious political party in the history of Nigeria, not because it lacks power, but because it lacks credibility. Nigerians know that hunger does not disappear because governors defect, inflation does not bow to propaganda, and hardship does not respond to political coercion. What they see instead is a widening gap between political theatrics and lived reality. In that gap stands Atiku Abubakar, a constant reminder that an alternative voice still exists and that the idea of a one-party state cannot survive where hope remains alive.

Let me say this unapologetically: the one-party project being pursued by the ruling party is dead on arrival. It is dead because Nigerians are politically conscious. It is dead because votes do not move with defections. And above all, it is dead because Atiku Abubakar remains standing, indefatigable, resilient, and central to the national conversation. As long as he continues to challenge bad governance and embody opposition, democracy in Nigeria will continue to breathe. And that, more than anything else, explains why so many are desperately trying and failing to stop him because Atiku Abubakar is a phenomenon and a force that cannot be stopped in 2027…

Dr. Sani Sa’idu Baba writes from Kano, and can be reached via drssbaba@yahoo.com

Related

Renowned Academic, Lawyer, Prof Afe Babalola, Bags PAWA’s Top Award

Adding Value: Be Intentional in Carrying Your Cross by Henry Ukazu

APC Drops Uzodinma As National Convention Chairman, Names Masari As Replacement

A Holistic Framework for Addressing Leadership Deficiencies in Nigeria, Others

Daredevil Smugglers Kill Customs Officer in Ogun

Tali Shani vs Mike Ozekhome: How a Legal Mole-Hill Was Turned into a Mountain

Glo Boosts Lagos Security with N1bn Donation to LSSTF

Senate Passes Electoral Bill 2026, Rejects Real-time Electronic Transmission of Results

Fight Against Terrorism: US Troops Finally Arrive in Nigeria

Legendary Gospel Singer, Ron Kenoly, is Dead

Glo Leads in Investments, Performance As NCC Sets New Standard for Telecoms

Wike Remains Undisputed Rivers APC, PDP Leader, Tinubu Rules

Memoir: My Incredible 10 Years Sojourn at Ovation by Eric Elezuo

Court Restrains NLC, TUC from Embarking on Strike, Protest in Abuja

Trending

-

Headline3 days ago

Headline3 days agoSenate Passes Electoral Bill 2026, Rejects Real-time Electronic Transmission of Results

-

National3 days ago

National3 days agoFight Against Terrorism: US Troops Finally Arrive in Nigeria

-

Featured4 days ago

Featured4 days agoLegendary Gospel Singer, Ron Kenoly, is Dead

-

National6 days ago

National6 days agoGlo Leads in Investments, Performance As NCC Sets New Standard for Telecoms

-

Headline4 days ago

Headline4 days agoWike Remains Undisputed Rivers APC, PDP Leader, Tinubu Rules

-

Featured6 days ago

Featured6 days agoMemoir: My Incredible 10 Years Sojourn at Ovation by Eric Elezuo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCourt Restrains NLC, TUC from Embarking on Strike, Protest in Abuja

-

Featured3 days ago

Featured3 days agoExpert Tasks Youths on Education, Skills Acquisition