Opinion

The Oracle: The NASS Cannot Amend the Constitution Through the Back Door (Pt. 2)

Published

2 years agoon

By

Eric

By Mike Ozekhome

INTRODUCTION

SECTIONS 84 AND 318 OF THE CONSTITUTION CONSIDERED (Continues)

Last week, we commenced our analysis of sections 84(12) and 318 of the 1999 Constitution. Today, we x-ray these sections further to demonstrate that the sections have been so gravely misinterpreted that the NASS could frontally assail the sanctity of the Constitution by enacting section 84(12) of the amended Electoral Act.

More significantly, we must look at the definition of “public officer” in part 1 of the 5th schedule of the Constitution. There, a “public officer” is defined as “a person holding any of the offices specified in part II of this schedule. The person holding the said offices specifically include, amongst others, the President; Vice President; Senate President and his Vice; Speaker of the House of Representatives; Governor; Deputy Governor; CJN; Justices of the Supreme Court; Appeal Court; Attorney General of the Federation and of States; Ministers and Commissioners; SGF; Ambassadors; Chairman; Members and Staff of CCB/CCT; of LGCs; Statutory corporations and companies in which the federal or state Governments or LGCs have controlling interest.”

This category of persons therefore fall within the scope of “public officers” and “public servants”. I humbly submit therefore that political appointees fall within the scope of public servants, such as to enjoy whatever favours are granted to persons within the public service of the Federation or of the State. “Service” is defined by by the Cambridge Dictionary as “as helping or doing work for someone”; “or providing a particular thing that people need”.

The word “includes” as defined Meridian Webster Dictionary, means “to take in or comprise as a part of a whole or group”. It becomes clear therefore that section 318 did not exhaustively list all those envisaged as “public servants”. Those listed merely comprise of “a part of a whole or group”, and nothing more. Can anyone seriously argue that ministers, Commissioners and such persons who are in the “service” of the Federation and States in different capacities are therefore political appointees not then in the public service of such governments? I humbly submit that the cases of DADA V ADEYEYE (2005) 3 NWLR (920) 1; ONI V FAYEMI (supra); WILSON V AG FEDERATION (supra); AG BENDEL STATE v AIDEYAN (supra); ADAMU V TAKORI (supra); have been grossly misapplied and misinterpreted exponents of the now struck down section 84(12).

In any event, why should the NASS be involved in legislating for political parties as to who should be their contestants or voting delegates, thus restricting their constitutionally guaranteed rights? In deepening the plenitude and amplitude of democracy, are the political parties not entitled to be accorded the freedom and latitude to regulate their own activities? I think they are.

Why then should the NASS make a law discriminating against political appointees when they themselves are free to contest, vote and be voted for as delegates at the same congress and conventions? How fair is that, on both moral and legal grounds, aside its unconstitutionality as I have strenuously pointed out above?

NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN VOTING AT GENERAL ELECTIONS AND VOTING AT POLITICAL PARTY CONGRESSES OR CONVENTIONS

I have heard the argument that the eligibility to vote or be voted for only affects general elections, and not elections at party congresses or conventions. I humbly disagree. Voting is voting; and election is election, whether at a general election, or at an election to elect candidates of political parties at party conventions or congresses. Both have to do with exercising one’s right to make a choice as between two or more candidates at an election through the ballot, or a show of hands. This is clear from the provisions of sections 82, 83 and 84 of the Electoral Act, 2022 (as amended). As in any general election, election by a political party at its congress or convention is invalid without the involvement of INEC. “Every registered political party shall give INEC 21 days notice of any convention, congress, conference or meeting convened for the purpose of ‘merger’ and electing members of its executive committee, other governing bodies or nominating candidates for any of the elective offices specified in this Act” (section 82(1)). See also sections 82 (2) and 82 (4).

The clincher is found in sections 82 (5), which provides that “failure of a political party to notify the Commission as stated in subsection 1 shall render the convention, congress, conference or meeting invalid”.

The non-observance of this critical provision was part of the reasons both the Court of Appeal and Supreme Court declared the votes cast at the 2015 APC primaries in Zamfara state “wasted votes”. I personally handled both cases against the APC. The Supreme Court agreed with my invocation of the doctrine of “consequential relief”, which I had commended to it, and ordered that the CANDIDATE of the political party (NOT the POLITICAL PARTY) that had the next highest number of votes and constitutional spread in the local Government Areas of Zamfara State should produce the next Governor. That was how Dr Bello Mohammed Matawalle became Governor of Zamfara State under the platform of the PDP. See APC & ANOR VS. KABIRU MARAFA & 170 ORS (2020) 6 NWLR (Pt 1721) 383; APC & ORS VS KARFI & 2 ORS (2017) LPELR – 47024 (SC).

This point becomes clearer when one reads section 84 (3) of the Electoral Act, 2020, as amended. It prohibits a political party from imposing nomination qualification or disqualification criteria, measures, or conditions on any aspirant or candidate for any election in its Constitution, guidelines, or rules for nomination of candidates for elections, except as prescribed under section 65, 66, 106, 107, 131, 137, 177 and 187 of the Constitution. Why will the same NASS audaciously ignore section 84 (3) and make section 84 (12) and (13) in the same Act to bar certain persons from contesting in those same elections which it had warned political parties not to go into, when the Constitution itself has not specifically provided for such? Respectfully, the provision of section 84(12) is not only strange, but bizarre.

We must bring in here the rule of statutory interpretation, to the effect that the provisions of the Constitution are to be read as a whole; and not in parts. Can such critics argue that the same Constitution will take away with the left hand in sections 84 (12) and 318 what it has itself donated in sections 40, 42, 65 (1) and (2), 66 (1), 106, 107 (1), 137 (1) (g), 147 (4), 182 and192 (3), thereof? Can it be argued that the same section 84 which in it sub-section (3) forbade political parties from imposing nomination qualifications or disqualifications criteria, or impose conditions on aspirants or candidates for any election, will turn around in subsections 12 and 13 to outrightly ban such candidates from voting or being voted for, simply because they are political appointees? I think not. See the cases of Nafiu Rabiu v. The State (1980) 8-11 SC-130; Abegunde v. Ondo State House of Assembly & Ors (2015) LPELR-24588 (SC), wherein the Supreme Court emphasized the need to read provisions of the Constitution together as a whole and not in parts.

Some people have cited in aid of their arguments the provisions of section 228(a) of the 1999 Constitution which provides that:

“The NASS may by law provide guidelines and rules to ensure INTERNAL DEMOCRACY within political parties, including making laws for the conduct of party primaries, party congresses and party conventions”.

This section actually encourages INTERNAL DEMOCRACY within political parties, which is designed to open up the political space and give every member a feeling of belonging. It was never designed or intended to restrict such members from voting and being voted for. The section actually frontally defeats section 84 (12) and (13) of the Electoral Act, 2022, as amended, and renders them unconstitutional, null and void.

THE JUDGMENT OF THE HIGH COURT IN UMUAHIA

It is with the solid background of the law and constitutionalism espoused above that I totally agree with the judgment recently delivered by Honourable Justice Evelyn Anyadike of the Federal High Court, Umuahia Division. She scored the bull’s eye in striking down the offensive subsection 12 of section 84 of the new Electoral Act in Suit No. UM/CS/26/2022: CHIEF NDUKA EDEDE V AG FEDERATION.

Most critics have never even cared to read the full order made by Justice Anyadike, so as to understand its true import and purport. She did not just restrict her order to only political appointees as is erroneously widely believed. She actually extended it to “any political appointee, political or public office holder”, as envisaged (according to these critics) in sections 84 and 318 of the 1999 Constitution. She actually aligned her order with these sections with the intention to deepen, widen and liberalize the political space. She thus held as follows:

“1. I Declare that Section 84(12) of the Electoral Act, 2022, cannot validly and constitutionally limit, remove, abrogate, disenfranchise, disqualify, and oust the constitutional right or eligibility of any political appointee, political or public office holder to vote or be voted for at any Convention or Congress of any political party for the purposes of nomination of such person or candidate for any election, where such person has “resigned, withdrawn or retired” from the said political or public office, at least 30 days before the date of the election”.

2. I Declare that the provisions of Section 84(12) of the Electoral Act, 2022, which limits, removes, abrogates, disenfranchises, disqualifies, and ousts the constitutional right and eligibility of any political appointee, political or public office holder to vote or be voted for at any Convention or Congress of any political party for the purposes of nomination of such person or candidate for any election, where such person has “resigned, withdrawn or retired” from the said political or public office, at least 30 days before the date of the election, is grossly ultra vires and inconsistent with Sections 6(6)(a) & (b), 66(1)(f), 107(1)(f), 137(1)(g) and 182(1)(g) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended) and therefore unconstitutional, invalid, illegal, null, void and of no effect whatsoever.

3. I hereby nullify and set aside Section 84(12) of the Electoral Act, 2022, for being unconstitutional, invalid, null and void to the extent of its inconsistency with Sections 66(1)(f), 107(1)(f), 137(1)(g) and 182(1)(g) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (as amended).

4. I hereby order the Defendant (The Attorney General of the Federation) to delete the provisions of Section 84(12) from the Electoral Act, 2022, with immediate effect.”

I respectfully agree with this judgment which remains valid until set aside by a higher appellate court. See the cases of AGBON-OJEME V. SALO-OJEME (2020) LPELR 49688(CA); NKWOKEDI & ORS V. OKUGO & ORS (2002) LPELR-2123(SC); EKPE V. EKURE & ANOR (2014) LPELR-24674(CA); UNITY BANK V. ONUMINYA (2019) LPELR-47507(CA). We shall continue our discourse next week, by God’s grace.

FUN TIMES

“Four men are in the hospital waiting room because their wives are having babies. A nurse approaches the first guy and says, “Congratulations! You’re the father of twins.” “That’s odd,” answers the man. “I work for the Minnesota Twins!” A nurse then yells the second man, “Congratulations! You’re the father of triplets!” “That’s weird,” answers the second man. “I work for the 3M company!” A nurse goes up to the third man saying, “Congratulations! You’re the father of quadruplets.” “That’s strange,” he answers. “I work for the Four Seasons hotel!” The last man begins groaning and banging his head against the wall. “What’s wrong?” the others ask. “I work for 7 Up!”-Anonymous.

THOUGHT FOR THE WEEK

“The illegal we do immediately. The unconstitutional takes a little longer.” (Henry Kissinger).

Related

You may like

By Prof Mike Ozekhome SAN

INTRODUCTION

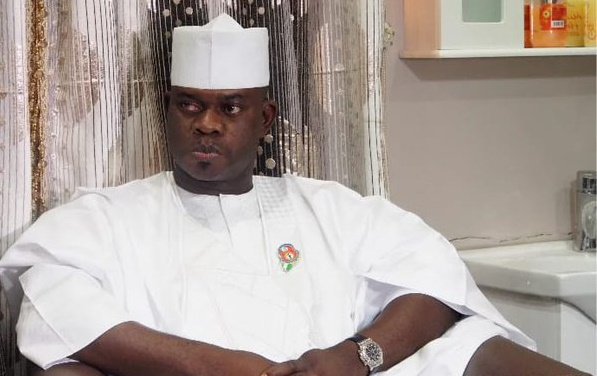

The nation has been agog with news of the ongoing face-off between the EFCC and the immediate past Governor of Kogi State, Alhaji Yahaya Bello and the others over the (EFCC)’s attempt to arrest Bello in connection with alleged official corruption involving the sum of 80.2 billion naira which he allegedly misappropriated while in office for eight years as Kogi State Governor.

Accusations and counter-accusations have raged back and forth between both camps (with not a few officious by-standers proffering gratuitous, ill-informed advice in the guise of opinions). As usual, the truth is always the first casualty. In this case, it is worsened by the fact that the matter is the subject of on-going litigation before at least two different courts: a High Court in the former Governor’s home State of Kogi and the Federal High Court in Abuja. The situation has been compounded by the order of injunction granted by a Kogi State High Court restraining the Commission from arresting or attempting to arrest the former Governor. The alleged breach of the order so irked the judge who issued it that he apparently had no option but to cite the EFCC boss for contempt. That order has been stayed by the Court of Appeal. Because these proceedings are ongoing, no more will be said on them.

Let me stress here that I am neither on the side of Yahaya Bello, nor that of the EFCC, or the Government of Kogi State whose funds are allegedly at the heart of the dispute. I will not cry more than the bereaved. My intervention here is limited to the legal ramifications and propriety of the steps taken so far by both sides of the divide.

BACKGROUND

Before Bello’s Abuja house was raided in a gestapo-like manner on April 17, 2024, Bello had, believing that his fundamental human rights were being threatened, approached a Kogi State High Court seeking an interim restraining order against the EFCC (Commission) pending the determination of a substantive suit before the court.

Justice Isa Abdullahi (presiding), who was satisfied with the grounds upon which the relief was sought, on February 9, 2024, gave an interim restraining order against the EFCC from taking any action against Bello, pending the determination of the substantive matter.

The Commission, dissatisfied, approached the Court of Appeal, Abuja, on March 11, 2024, requesting the appellate court to set aside the interim restraining order. It argued that the lower court lacked the requisite jurisdiction to assist Bello escape his deserved justice. It also argued that Bello could not stop the Commission from carrying out its statutory duties, nor use the lower court to escape its invitation, investigation and possible prosecution as the court’s order directed.

The Appeal Court adjourned hearing to April 22, 2024, while refusing to hear EFCC’s application for a stay of the order of interim injunction. In further affirming its earlier interim orders, the Kogi State High Court on April 17, 2024, delivered judgment in the substantive suit and directed the Commission to first seek the leave of the Court of Appeal before taking further steps against Bello. It granted some injunctive reliefs against the Commission “from continuing to harass, threaten to arrest or detain Bello”. The court directed the Commission to file a charge against Bello in an appropriate court if it had some reason to do so. The Commission later obtained a warrant of arrest against Bello from the Federal High Court presided over by Justice Emeka Nwite. On April 22, the anti-graft agency filed a notice of withdrawal of its appeal, predicating it on the ground that events had overtaken the appeal; while admitting that the appeal was filed out of time.

Bello’s team promptly challenged the arrest warrant by the Federal High Court and Justice Emeka Nwite has adjourned for his ruling on the propriety of his warrant of arrest against Bello.

WHEN AND HOW TO SUMMON A SUSPECT FOR INVESTIGATION BY LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES

I condemn any brute and sensational arrest of a suspect such as Bello. It does not matter the station of life of such suspect, whether high or low. Hooded DSS operatives once did it to some Justices of the Supreme Court and other Judges on 8th October, 2016, when they viciously and savagely broke into their homes in the wee hours of the morning. I had condemned it in very strong words. (See https://www.bellanaija.com/2016/10/falana-ozekhome-melaye-react-to-arrest-of-judges-by-dss/) (October 10, 2016). Some of the victims like Justice Sylvester Ngwuta, JSC (of blessed memory) never recovered from the shock. He later died. Others took early premature retirement. Was the Commission therefore right in attempting to arrest Bello in the manner it did as some commentators have approved in their writeups? I think not. The relevant provisions of the law such as Sections 8(1) of the Anti-Torture Act, 2017; Section 6 of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) 2015 (applicable in Abuja, the FCT); and Section 35(2)&(3) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999, as amended, the sum total of which enjoin the fair and humane treatment of a suspect whether during his /her arrest, investigation, detention pending trial and arraignment. Was a bench warrant necessary against a suspect on whom charges had not been served as in the Bello scenario? I think not. Let us look at some decided cases on this.

In USANI V. DUKE [2006] 17 NWLR (Pt.1009)610 the Court of Appeal held thus:

“A bench warrant is a discretionary power of a court invoked to secure the attendance as in this case of an unwilling witness under the threat of contempt of court to give evidence on any area of a suit within his knowledge. It is not a discretion which is exercised as a matter of course. The court has to be satisfied that there is absolute necessity to procure the appearance of the witness in court. The lower tribunal based its refusal to issue bench warrant on non-compliance with section 229(2) of the Evidence Act.” Per ADEKEYE, J.C.A. (P. 38, paras. B-E)”.

In APUGO V. FRN (2017) LPELR-41643 CA, the Court of Appeal eruditely held that:

“Section 382 (4) and (5) of the ACJA provides for how to serve a Charge and notice of trial on a Defendant, who is not in custody, … In this case, the Respondent had filed a motion exparte under section 382(5) of the ACJA 2015 to serve Appellant by substituted means. That motion was not argued, but the trial court jumped the gun and ordered for the bench warrant to arrest the Appellant: and when it found out that that was wrong, it suspended the implementation of the bench warrant (instead of setting it aside) the trial court yet still ordered the Appellant to appear on the next adjourned date to answer to the Charge against him, pursuant to section 87 of the ACJA 2015. As earlier discussed and held above, I do not think the trial court had the vires to make such order, in the circumstances as I think it went beyond its role as impartial adjudicator, to that of the Prosecutor or Police or EFCC to forcefully produce the Accused person, without serving him with any charge or notice of trial. See NWADIKE v. State (2015) LPELR- 24550 (CA), Ededet v. State (2008) 14 NWLR (Pt 1106) 52. I do not think section 87 of the ACJA 2015, can apply without recourse to section 382 of the same Act which requires a Defendant to be served personally or by substituted means with the charge or information and notice of trial. I believe it is upon compliance with section 382 (3) (4) and (5) of the Act where there is a pending charge, that the trial court can have the powers to apply the section 87 of the Act which says: “ A court has authority to compel the attendance before it of a suspect who is within the jurisdiction and is charged with an offence committed within the state Federal or the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, as the case may be or which according to law may be dealt as if the offence had been committed within jurisdiction and to deal with the suspect according to law”. Per MBABA J.C.A J.C.A (Pp. 46-48, paras. F-F)’’.

See also sections 113, 131, 394, 398 and 399 of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act 2015.

These domestic laws are reinforced by a regional (in fact, continental) statute – the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights – Article 7 of which obliges the State (and all other persons) to respect the rights of every individual to have his (or her) cause heard. This right encompasses the following, inter alia:

(i) The right to appeal to competent national organs against violating his fundamental rights;

(ii) The right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty by a competent tribunal;

(iii) The right to defence including by Counsel of one’s choice;

(iv) The right to be tried within a reasonable time by an impartial court or tribunal.

The importance of this statute is often overlooked by many Nigerians because, apart from the Constitution, it is superior to virtually every local or municipal law – including the EFCC (Establishment) Act itself. See ABACHA VS FAWEHINMI (2000) 6 NWLR part 660, pg 228, where the Supreme Court held that the Charter possesses “greater vigour and strength than any other domestic statute… (accordingly if there is a conflict between it and another statute its provisions will prevail over those of the other Statute”)

It is in this context that I believe the Commission’s tactics in attempting to arrest Bello ought to be situated. While no one quarrels with the Commission’s full mandate to tackle economic crimes, the way and manner in which it does so must however, not portray any impunity or suggest that it is above the law. After all, the Commission’s motto is “No one is above the Law”. To that extent, the fact that the person at the centre of the present controversy is a former Governor is irrelevant: it merely hugs the headlines for that reason. Afterall, he has since lost his immunity under section 308 of the 1999 Constitution, upon vacating office. However, once a person has been charged to court as Bello has, he becomes the subject of the court which becomes seized of the matter. His availability in court is thereafter controlled by the trial court, and not another through a bench warrant.

Many a time, it is argued that the court cannot restrain government agencies from arresting, investigating or prosecuting suspects. This is far from the truth as it depends on the facts of each case. For example, the Court of Appeal in OKEKE v. IGP & Ors (2022) LPELR-58476(CA) 1 at Pp. 9 paras. A, Per NWOSU-IHEME, J.C.A (as she then was), relied on a decision of the same Court to hold that the Police can be restrained from the improper use of its powers. In the unreported case of LUNA V. COMMISSIONER OF POLICE RIVER STATE POLICE COMMAND in Appeal No CA/PH/216/2004, the Port-Harcourt Division of the intermediate court held:

“… Notwithstanding the power of the Police as spelt out in Sections 4 and 24 of the Police Act, where this Power is improperly used, the Court can stop the use of the power for that improper purpose, as that would no longer be covered by Section 35(1) (c) of the 1999 Constitution. In other words, an order restraining the Police from arresting on some particular occasion or for some particular improper purpose may be made by the Court.”

THE EVILS OF MEDIA TRIAL

The Yahaya Bello case evinces a clear case of media trial which should never be. The notion “Media Trial” or “Trial by Media” got its name in the United States of America during the period of 19th Century and became familiar with the Indian legal system in the famous, case of K.M Nanavati v. State of Maharashtra AIR 1962 SC 605.

I have, on my part, always kicked against media trial, for it presumes a person guilty even before his trial in open court. At the first National Anti-Corruption Stakeholders’ Summit held in 2017 with the theme, “Building national anti-corruption consensus in a multi-agency Environment”, which was organised by the Commission at the EFCC Academy, Karu, Abuja, I made the following remarks:

“…. All my life that is what I have done. I take it very seriously when we talk about the issue of rule of law. I do not believe in media trial. For example, a case is being investigated in EFCC, the suspect is being interrogated, tomorrow it is in a particular newspaper as to the statement made by that suspect. That suspect may never be tried. Even if he is arraigned and tried, he may never be found guilty but you have destroyed his image, his reputation. We should run away from that, it is not good. There is the need in this anti-corruption war to make an example; just one example with one person in government. I am aware of many, many petitions against people in this government”. See Nigerian Tribune edition of 28th March, 2017. (https://tribuneonlineng.com/stop-media-trial-suspects-ozekhome-tells-efcc/).

I had also in 2017, written to the Commission and presented a paper at CACOL Roundtable, titled “The A-Z and 24 “Dos” and “Don’ts” of how to fight corruption”. (See Daily Times of 24th April, 2017 – https//issuu.com/dailytimes. ng/docs/dtn-24-04-17/19). This paper is still relevant today, as it represents my contribution to the fight against corruption which I personally believe in. But, such war must be within the confines of the law. At the time of my lecture, the Commission under Ibrahim Magu had not made any attempt to try government functionaries; and I challenged it to do so. I do not know, whether it was my wakeup call that made the Commission to finally start charging people in government, especially Governors and Ministers, to court. Or, do you? I had also clashed with the former Chairman, Magu, on this sore issue on 19th December, 2017, at the Federal High Court, Abuja, at its end of year event. (See: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/12/anti-graft-war-magu-ozekhome-clash-fhc-end-year-event/)

THE DANGER INHERENT IN MEDIA TRIAL

Media trial which has become the order of the day in Nigeria is simply the act of using media coverage to vilify and portray a suspect or an accused person as a criminal, even without trial. In the context of Nigerian jurisprudence, a trial is an avenue to challenge the innocence of an accused person. A Media trial is an improper use of the media to tarnish the image of an accused person before, during or after a trial. It is used to dampen the resilient spirit of an accused person. The Commission used this craft greatly, especially during the tenure of Ibrahim Magu; and it greatly chipped away some nobility in its patriotic war against corruption.

The public applauds media trial. The downtrodden guffaws when the rich also cry. With this, there are more media convictions than actual convictions in the courtroom. Unfortunately, Yahaya Bello, has become the latest victim of media trial. If he is eventually acquitted, people will attribute his non-conviction to “a complicit judiciary”, (the whipping orphan).

Bello’s present ordeal may have undoubtedly brought some people immense joy. This submission has been tacitly corroborated by the Commission’s Chairman, very hard working and dedicated Mr Olanipekun Olukoyede, who stated, in a now-viral video, that the former Governor of Kogi State declined to come to the agency’s office because he complained that a female Senator had allegedly gathered journalists together to humiliate him anytime he appeared in the office of the agency for interrogation. Obviously, Bello was scared of media trial; so he avoided it. The evils of media trial are galore.

Media trials, especially in places like Nigeria, can be highly dangerous and prejudicial to a fair trial for several reasons:

1. Presumption of Innocence: Under the provisions of Section 36(5) of the 1999 Constitution, every accused person is presumed innocent until he is found guilty. Media trials often disregard the principle of “innocent until proven guilty.” When suspects are portrayed as guilty before they have had a fair trial, it can prejudice public opinion and undermine the legal process. The Muhammadu Buhari government specialised in this Goebel’s propaganda style under its “Name-and-shame” mantra. Such removes the Anglo-Saxon accusatorial system we operate and whimsically substitutes it with the French inquisitorial system.

By the provisions of section 36(5) of the 1999 Constitution, every person who is charged with a criminal offence shall be presumed to be innocent until proven guilty. This is unequivocally the position of the law, and has not changed. Article 7(1) (b) of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights 1981, also guarantees the presumption of innocence when it states as follows: every individual shall have the right to fair-hearing, that is; to have his cause heard including a right to an appeal, to be presumed innocent until proven guilty by a competent court or tribunal, and also the right to defence, including the right to be defended by Counsel of his choice. These are provisions that guide the trial of any person suspected to have committed a crime. It further extends to the right to be tried within a reasonable time by an impartial court or tribunal Thus, the presumption of innocence is the legal principle in criminal cases that one is considered innocent until proven guilty. This therefore means that until a judicial pronouncement is made, a suspect or defendant as the case may be should be treated with dignity as an innocent citizen. Anything to contrary would amount to a breach of the fundamental rights of the individual. See the cases of Tosin .v. State (2023) LPELR-59635 (CA); Onyeka .v. State (2023) LPELR-60520 (CA) and OLALERE .V. STATE (2022) LPELR-58103 (CA).

2. Mob Mentality: Inflamed by sensationalized media coverage, the public can form strong opinions and even resort to mob justice. This can lead to violence, whether against the accused or others associated with them.

3. Interference with Legal Proceedings: Judges do not live on the island, Venus, Moon, Neptune or Mars. They live on earth and interact with members of the society. Media attention can influence judges, potentially leading to unfair trials. It can be difficult for a defendant to receive a fair trial when public opinion has been heavily influenced against him by biased media coverage. In the case of Rajendra Jawanmal Gandhi v. State of Maharashtra, (1997) 8 SCC 386, the Supreme Court of India noted that a trial by press, electronic media, or public agitation is the exact opposite of the rule of law. It held further that Judges should protect themselves from such pressure and scrupulously adhere to the rule of law since failure to do so could result in a miscarriage of justice. Parties are entitled by the Constitution to a fair trial in a court of law by an unbiased tribunal that is not swayed by popular culture or media coverage.

4. Violation of Privacy and Dignity: Suspects, especially those who are later found innocent, can suffer irreversible and irreparable damage to their reputation, mental health, and livelihood due to intrusive media coverage. See section 37 of the 1999 Constitution.

5. Impact on Investigation: Media trials can jeopardize investigations by prematurely revealing sensitive information or influencing potential witnesses or suspects.

6. Undermining Trust in the Justice System: When the public perceives that justice is being served through media sensationalism rather than through fair legal processes, it can erode public confidence and trust in the judiciary and law enforcement agencies. This is the situation our judiciary has found itself. When a wealthy man who is accused of looting the state treasury is acquitted of corruption-related charges, some members of the public readily accuse the judiciary of complicity. Because some Nigerians do not trust the judiciary, they believe, courtesy of media trial, that the judiciary is a tool of the ruling class to consolidate or legitimize their hold on power and the society.

7. Political Manipulation: In some cases, media trials may be used as a tool by powerful interests to manipulate public opinion, discredit political opponents, or distract from other issues. The ongoing trial of the former CBN Governor, Mr. Godwin Emefiele, is a perfect example. Virtually all the bad economic policies of the President Buhari government have been attributed to the leadership of the apex bank under Emefiele and the Bank Managing Directors. Was this really the case? Was Buhari not in charge?

There are many instances when suspects who had been subjected to needless media trial were later vindicated by courts of law. Let us see some examples:

(i) The siege and break-in through the roof on the residence, ‘abduction’ and subsequent arrest and arraignment by the EFCC in a clearly orchestrated media trial of former Governor Rochas Okorocha of Imo State. He was later discharged and acquitted.

(ii) The trial and subsequent discharge and acquittal, only last month, by the Federal High Court sitting in Lagos, of the former Director-General of NIMASA, Mr Patrick Akpobolokemi, after over eight years on trumped up charges of conspiracy, stealing and fraudulent conversion involving the sum of ₦8.5billion. The court, coram, Justice Ayokunle Faji, upheld his Counsel’s no-case submission that the Commission had failed to make a prima facie case requiring him to enter his defence in respect of four out of six charges laid against him by the Commission. This was after eight years of gruesome trial and media hype, with Akpobolokemi, being physically dragged on the ground in one instance.

The discharge and acquittal earlier this year of the erstwhile Attorney-General of the Federation and Minister of Justice under the Administration of the former President Goodluck Jonathan, Mr Mohammed Bello Adoke and some companies by the Federal High Court, Abuja (Ekwo, J) and the High Court of the FCT (Kutigi J), on charges of money laundering and abuse of office after over four years of hyped media trial which the latter court strongly condemned and for which it excoriated the Commission for the slip-shod manner in which it undertook what, to all intents and purposes, was a persecution rather than precaution. The investigation into the alleged offences was anything but diligent, forcing the Commission’s own Counsel (to his credit) to throw in the towel and admit that he could not, in all honesty, support their continuing trial. I had gotten vacated and set aside the Bench warrant earlier issued against Adoke by Danlami Zama Senchi (now of the Court of Appeal). I was the one who also argued Adoke’s bail applications before Justices Inyang Ekwo and Idris Legbo Kutigi.

Also apposite are the nasty experiences of former Senator Dino Melaye whose cases I also handled; and that of the Supreme Court Justices way back in 2016 (even though the latter was perpetrated by a sister agency, the DSS) .

What about late High Chief Aleogho Raymond Dokpesi? He was later discharged on a no case submission after over eight years of horrid trial in which I secured his bail in 2015! The cases of Col. Sambo Dasuki, El Zakzaky and Elder Godsday Orube are well too known to enlist elucidation here.

The Commission surely had full knowledge of the ex-parte order made by the Kogi State High Court which had restrained the Commission from arresting Yahaya Bello. Yet, it laid a siege on Bello’s Abuja residence. The entire drama (which played out in the full glare of television cameras) was nothing short of disdain for the rule of law and the sanctity of court orders. It is trite law that, until a valid and duly issued court order is set aside either by the same or another court of superior or co-ordinate jurisdiction, it must be obeyed and complied with to the hilt.

The proper remedy open to the Commission which disagreed with the order was to challenge it and seek its reversal at the appellate court as it later did, and certainly not to flout or disobey it under any disguise. Needless to say that disobedience to court orders is a feature of self-help only in a society where anything goes; where life is poor, solitary, nasty, brutish and short, to quote the English Philosopher, Thomas John Hobbes. We must never allow Nigeria to degenerate to such a nadir state where government institutions disobey court orders with impunity. That is a ready recipe for organized disenchantment.

Indeed, so important is obedience of court order that it is given constitutional imprimatur in Section 287 of the 1999 Constitution.

In this regard, in FCDA V KORIPAMO-AGARY (2010) LPELR-4148 (CA), Mary Ukaego Peter-Odili, J.C.A (as he then was) held that:

“The Court frowns at disobedience of its orders; particularly by the executive branch of government and has used rather harsh language such as ‘executive lawlessness’, in describing such acts of disobedience. On the application of an aggrieved party, the Court has in appropriate cases, not hesitated to exercise its coercive power to set aside such acts done in disobedience of its order and restore the parties to the position they were before such disobedience. The rationale for this course of action by the Court is to ensure the enthronement of the rule of law rather than acquiesce in resorting to self-help by a party. The Court also has the power of sequestration and committal against persons disobeying its orders. It is an overgeneralization and therefore wrong to say that an act done in disobedience of a Court order is an illegality”.

See also ALL PROGRESSIVE CONGRESS & 2 ORS V HON DANLADI IDRIS KARFI & 2 ORS [2018] 6 NWLR (Pt 1616) 479, 493 SC and EZEKIEL-HART V EZEKIEL-HART [1990] NWLR (pt 126) 276. where the Supreme Court upheld the same principle.

By the same token, it is also settled that once the court is seised of a matter, it becomes dominus litis (master of the proceedings) and no party is allowed to take any step that will either overreach the court or the other party or present the court with a situation of fait accompli or complete helplessness in which whatever orders it makes might either be rendered nugatory or unenforceable. Such will be an affront on the court. See Ojukwu v. Governor of Lagos State (1986) 3NWLR (Pt 26) 39.

CONCLUSION

The judgment delivered by the High Court of Kogi State on April 17, 2024, finally vindicated Yahaya Bello on this issue as the court pointedly held:

“Thus, the serial action of the Respondent, dating back to 2021, right up to 2024, targeted against the applicant, has corroded their legitimate statutory duties of investigation and prosecution of financial crimes. These collective infractions on the rights of the applicant border on infringement of his fundamental right from discrimination”.

Central to the court’s rebuke is the condemnation of the anti-graft agency’s reliance on media sensationalism, characterized as a form of trial by public opinion. The court firmly asserted the principle that the agency’s role is not to act as both prosecutor and Judge simultaneously; but rather to present evidence within the confines of due procedure. This critique underscores the imperative of upholding the rule of law and granting individuals, including Bello, their rightful day in court devoid of extrajudicial influences.

Beyond the specifics of Bello’s case, there is need for a paradigm shift whereby agencies such as the EFCC, Police, ICPC, DSS et al, adopt a more public-friendly stance akin to their counterparts in advanced jurisdictions such as the United States, the United Kingdom and many European states. The importance of viewing law enforcement as a Service rather than as a Force, underscores the necessity of cultivating public trust and confidence through transparent, law-abiding practices. I hereby emphasize and advocate (as I have always done), strong institutions; not strong men.

We must, therefore, strike a balance between reporting matters that are of public interest and respect for the dignity of persons. In India, the Law Commission in its 200th report, “Trial by Media: Free Speech versus Fair Trial under Criminal Procedure (Amendments to the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971)”, has recommended a law to debar the media from reporting anything prejudicial to the rights of the accused in criminal cases, from the time of arrest to investigation and trial.

No individual, regardless of his position or authority, is above the law. There is no exception in the sense that even those who are protected from prosecution by the immunity clause in section 308 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, as amended, will after vacating the office be answerable like all other citizens and subject themselves willingly or unwillingly to the law. By holding both governmental and non-governmental actors accountable to the law, a commitment to fostering a culture of accountability and respect for individual rights is built and maintained.

Be that as it may, the laid down procedures must be followed accordingly. Where such laid down procedures are not tenaciously complied with, it will become an agency of government dictating its own rules, procedures and modus operandi. This is only typical of an autocratic, despotic and dictatorial government which we do not operate. It is in the light of this that the Commission and all other agencies established by laws must ensure that they conduct their operations within the ambit of the laws that established them. The concept of rule of law entails that all actions of government must be carried out as spelt out by the law without any form of self-help. In an ideal society where everyone, the leaders, the followers and the law enforcement agencies follow the law, a pattern develops where there can be a reasonable expectation of what will occur in any given situation. And ultimately, this provides security and safety as people do not need to panic out of uncertainty or feel worried about any situation since what will happen is readily predictable.

In the light of these considerations, there is need for a reevaluation of law enforcement practices and a renewed dedication to upholding the rule of law. There must be a balance of the imperatives of justice with the protection of individual rights, particularly in the face of media scrutiny and public pressure.

For now, citizen Yahaya Bello wears the toga of victimhood and not of aggression. He should be allowed to have his fair day in court without the present needless ruckus and brouhaha.

PROF MIKE OZEKHOME SAN, CON, OFR, FCIArb, LL.M, Ph.D., LL.D., D.Litt, D.Sc. is a constitutional lawyer and human rights advocate

Related

My Dear Uncle,

Happy birthday Chief Mike Adenuga ! The Big Bull himself! Your life is a testament to resilience, determination and unwavering commitment to excellence.

You are certainly a titan amongst men, a visionary whose strides have reshaped industries and inspired countless dreams.

Your remarkable impact on Nigeria transcends mere success; it is a legacy of inspiration and transformation. Through your visionary leadership and entrepreneurial spirit, you have not only built a business empire but have also paved the way for countless others to dream big and achieve greatness.

Your influence has been profound. Your achievements serve as a beacon of hope, reminding me that with hard work and dedication, anything is possible.

As we celebrate another year of your remarkable journey, I am reminded of the words of Nelson Mandela:

“What counts in life is not the mere fact that we have lived. It is what difference we have made to the lives of others that will determine the significance of the life we lead.”

Dear Uncle your life is a testament to this profound truth.

As you continue to bring joy and laughter to the lives of countless people may the good Lord reward you with His grace and mercy .

Here’s to many more years of success, good health and continued impact.

Happy birthday, Uncle Mike

Related

Opinion

We Can All Learn Tolerance from Globacom and the Yoruba

Published

1 week agoon

April 28, 2024By

Eric

By Reno Omokri

When the Central Bank of Nigeria relocated some departments to Lagos, there was an uproar on social media. Tinubu wants to move everything to Yorubaland.

But now that the Nigerian Navy is moving its training base headquarters from Lagos to Onne, in Rivers State, there is silence online. Nobody is saying that the Chief of Naval Staff, who is from Enugu, is moving that critical infrastructure closer to his region. And that is the right thing to do. Onne is a better location for the navy.

Please note that the Naval Training Command headquarters is a more significant infrastructure, and has more human resources than the departments of the CBN that moved to Lagos.

Recall that some individuals tried to pull off a Yoruba nation agitation in Ibadan a few weeks ago, look at how their own Yoruba kith and kin clinically dealt with them. And not even by the Federal Government, but by the Oyo State Government, which is in opposition to the Federal Government. Elsewhere, secessionists are protected, and even celebrated by the local population, and the State Governments look the other way.

One man even boasted that, “They are not terrorists. I meet them and live with them.” Please note that this is a direct quote.

Let us learn to imbibe the tolerance of the Yoruba, and Nigeria will go well.

The Omoluabi culture of tolerance stems from their culture, not from their DNA, so it is something all of us can also learn. It a not a racial trait, like their ability to have more twin births than any group on Earth.

It is built on two platforms. Iwa, which means moral character (Omoluabi actually is short for Omo-ti-Olu Iwa-bi, meaning children that the Lord of moral character gave birth to).

The second platform is Ebi, meaning family. Omoluabi Yoruba are taught to uphold fraternal relations above money and power. And not just among Omoluabi, but with all peoples.

That is why, for example, Colonel Fajuyi rejected the offer to surrender Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi to rebellious Northern officers, and replace him as Military Head of State. He voluntarily chose to follow Ironsi to his death. That is a combination of the Iwa and Ebi ethos.

And it continued even after Fajuyi’s death. How?

After Ironsi and Fajuyi’s death, Fajuyi’s successor as Military Governor of the Western Region, Adeyinka Adebayo, looked after Ironsi’s children, who lived with him in his house. I bet you never knew that. Please, fact-check me.

Do you know the most Islamic state in Southern Nigeria? It is not Lagos. Please research it. The state with the highest percentage of Muslims in Southern Nigeria is Osun State.

Yet, the indigenes of that state voted for a man who is both officially a Christian and a Muslim as their Governor. Yes. Please fact-check me. Senator Ademola Adeleke regularly attends church and not so regularly attends mosques. At best, he is a Chrislamist. But officially, he has been tagged as a Christian in certain publications.

So, Osun has a Chrislam Governor, who just happens to be half-Igbo (Senator Adeleke’s mother was Igbo and he was born in Enugu), a Christian Deputy Governor, and a Christian Speaker. Please note that Osun recently changed Speakers, and I do not know the religion of the new Speaker, Prince Adewale Egbedun. But his predecessor, Timothy Owoeye, is a Christian.

Recently, I had cause to defend Chief Eric Umeofia over the attempts by some people to destroy his business, and I cautioned them to understand that he had 4,000 employees. Though this fellow is not from the Southwest, those who led the effort to save his reputation and business are from the Southwest.

This is the type of pan-Nigerian spirit that we can learn from the Yorubas as we all imbibe their Iwa and Ebi ethos.

And nowhere do we see that culture on display better than at Globacom. This is a company wholly owned by an Ijebu man, Dr. Mike Adenuga. Yet, even when there were prominent Ijebu and Yoruba artists who were the biggest singers in Nigeria at that time, Globacom deliberately chose to promote the principle of One Nigeria.

Sunny Ade was there. D-Banj was then the hottest artiste in Nigeria. Paul Play Dairo was at that time ruling the airwaves with Mo Sori Ire.

But Globacom ignored them. The company took a relatively unknown as at then group. They took P-Square, and made them the face of their brand. And they sent them to etiquette school. Glo had P-Square on billboards all over Lagos and Nigeria. You could not go from Ikoyi to Victoria Island without seeing a giant Goo billboard with Nigerian music stars.

Dr. Adenuga bought P-Square their first brand-new Mercedes G-Wagon. Then he bought them brand new Range Rovers.

As Glo ambassadors, P-Square were featured on CNN for the Glo with Pride campaign, which blew them up worldwide. They thereafter bought houses in America, and would have become even more prominent globally, until quarrels over business made the twins separate for almost five years, which affected their fame.

But then there happened to be a quarrel between one of them and Seun Kuti, and in the heat of the moment, Peter Okoya called his own father “a nobody”. Not Seun’s father. Fela was never a nobody. No. Peter Okoye referred to his own father as a nobody.

Such a thing can NEVER happen in Yoruba land. Never a thousand times. And if by mistake a Yoruba man dares do that, the community will beat him to a pulp the way Ibadan people beat the Yoruba nation agitators three weeks ago.

There is nothing wrong with Air Peace using an Isi-Agu costume as the uniform for their flight attendants. I defended them publicly. Please research it. My defence of Air Peace went viral.

But let me say here that if Air Peace had been owned by Dr. Adenuga, they would have taken a different approach.

Happy 71st birthday to one of Nigeria’s most outstanding entrepreneurs ever, bar none. Dr. Mike Adenuga Junior.

Related

Ikeja Electric Slashes Electricity Tariff for Band A Customers

Police Arrest Kidnap Suspects Who Slept Off After Abducting Pastor’s Wife, Others

Dele Momodu Speaks on EFCC, Yahaya Bello’s Case, Others

Yahaya Bello vs EFCC: The Tussle Continues

Yahaya Bello: Victim or Aggressor?

Accomplished Entrepreneur, Taiwo Afolabi, Revels at 62

A’IBOM GOVT PARTNERS FHA ON AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Nigerian Engineer Wins $500m Contract to Build Monorail Network in Iraq

WORLD EXCLUSIVE: Will Senate President, Bukola Saraki, Join Presidential Race?

World Exclusive: How Cabal, Corruption Stalled Mambilla Hydropower Project …The Abba Kyari, Fashola and Malami Connection Plus FG May Lose $2bn

Rehabilitation Comment: Sanwo-Olu’s Support Group Replies Ambode (Video)

Pendulum: Can Atiku Abubakar Defeat Muhammadu Buhari in 2019?

Fashanu, Dolapo Awosika and Prophet Controversy: The Complete Story

Pendulum: An Evening with Two Presidential Aspirants in Abuja

Who are the early favorites to win the NFL rushing title?

Boxing continues to knock itself out with bewildering, incorrect decisions

Steph Curry finally got the contract he deserves from the Warriors

Phillies’ Aaron Altherr makes mind-boggling barehanded play

The tremendous importance of owning a perfect piece of clothing

Trending

-

News6 years ago

News6 years agoNigerian Engineer Wins $500m Contract to Build Monorail Network in Iraq

-

Featured6 years ago

Featured6 years agoWORLD EXCLUSIVE: Will Senate President, Bukola Saraki, Join Presidential Race?

-

Boss Picks6 years ago

Boss Picks6 years agoWorld Exclusive: How Cabal, Corruption Stalled Mambilla Hydropower Project …The Abba Kyari, Fashola and Malami Connection Plus FG May Lose $2bn

-

Headline6 years ago

Headline6 years agoRehabilitation Comment: Sanwo-Olu’s Support Group Replies Ambode (Video)

-

Headline6 years ago

Headline6 years agoPendulum: Can Atiku Abubakar Defeat Muhammadu Buhari in 2019?

-

Headline5 years ago

Headline5 years agoFashanu, Dolapo Awosika and Prophet Controversy: The Complete Story

-

Headline6 years ago

Headline6 years agoPendulum: An Evening with Two Presidential Aspirants in Abuja

-

Headline6 years ago

Headline6 years ago2019: Parties’ Presidential Candidates Emerge (View Full List)